Women's Fashions of the 1700s

Dolores's interest in fashion history dates from her teenage years when vintage apparel was widely available in thrift stores.

The 18th-Century Fashion Revolution

The 18th century revolutionized fashion concepts as well as economic, political, and philosophical ideals. The stiff, formal, and elaborately ornate styles of the early 1700s gave way, by the end of the century, to simpler garb. The French aristocracy clung to the lavish displays of court fashion just as they held on to their luxurious lifestyles, despite changes in the economy. They ended up racking up debt as high as their hairdos.

As the century progressed, English styles influenced the formerly fashion-first French. Simpler garments based on pastoral life came into vogue in England and moved into Europe. In the late 18th century, English influence relied on a sense of propriety rather than the decadent ornamentation of the elite.

New technologies, materials, and communication offered the merchant class opportunity to wear stylish garments. By the mid-1760s, women's magazines offered even rural women glimpses of current styles. The introduction of cotton and faster production techniques gave women the ability to become fashion consumers.

The beautiful gowns associated with the French aristocracy were worn at court as ceremonial dress. The more comfortable clothing worn at home called "undress" gradually replaced the cumbersome, very expensive look of court dress. Where once the hoi-polloi looked to the aristocracy for style, the elite began to lose their luster.

At-a-Glance Fashion Changes

- New technologies speed up textile production

- France was greatest fashion influencer

- Court attire and hair became extreme and flamboyant

- Century ended with simple, neoclassical styles

Textiles and Trade

The clothing industry offered occupations in spinning, weaving, tailoring, dress making, glove making, lace making, for clothiers, and trade.

Europe produced wool and linen textiles. It imported silk from the Far East and cotton, chintz, and muslin from India. In the late 1700s, England exported fabric to the New World where raw cotton had become a commodity sent to England for production.

While the upper class had clothing made for them, commoners still spun, wove, and made their own garments. The urban underclass purchased used goods from dealers. Early in the century, clothing was very expensive but new inventions and the increased availability of cotton brought costs down in later years.

The flying shuttle, invented in 1733, increased the speed of weaving. In 1785, Cartwright's power loom made weaving even faster. Eli Whitney's cotton gin (1793), later improved by Hogden Holmes, was based on India's churka (an early cotton gin) which removed the seeds from the boll to speed up production. The machine led to America's dominance in the cotton market as well as the enslavement of millions of Africans.

Europe's beautifully patterned silks permeated style in the early 1700s. By the century's end, soft muslin from India replaced heavier garments.

Early 1700s

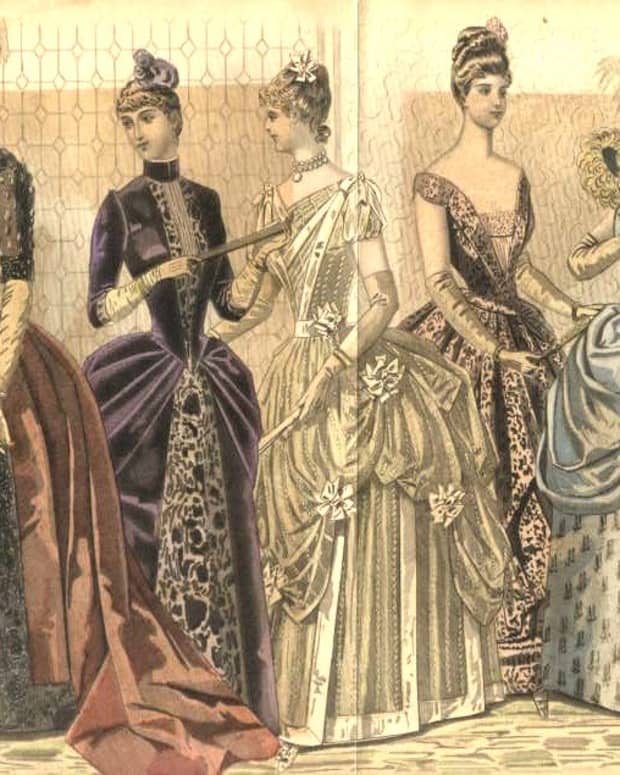

Slender, asymetrical curves and soft drapery dominated women's costumes of the early 18th century. France greatly influenced women's styles in clothing and the decorative arts.

The mantua was a gown made of one long piece of fabric draped over the shoulders. The loose-fitting bodice was not boned or stiffened. Worn without a corset, a mantua began as a comfortable garment but evolved over the years into a more formal gown. Fabric was drawn up and pulled back to reveal the petticoat. The silk damask fabric hung in soft pleats at the top to a belted waist and hung down into a train. The train was later taken up and draped.

Gown fabric featured bold, large-patterned silks, often contrasting with plain satins in soft blues and pinks, or dark browns and greens.

A short jacket-like version of a matua called a pet-en-lair fell to the knee early on then shortened as the century progressed.

Hoops came into vogue by 1710. Cone-shaped hoops made of whale bone (actually baleen) were sewn into heavy petticoats. By the 1720s, dome-shaped hoops increased the size of skirts.

At the time, petticoats could be plain or made of a luxurious material. Pulled-back gowns often revealed petticoats of contrasting fabric. Or a printed gown fabric was worn over a petticoat made of plain material in the same color as the gown.

Bell-shaped sleeves ended at the elbow and featured lace or ruffles.

Read More From Bellatory

Court etiquette demanded rigid, formal attire. Women wore corsets that accentuated an extremely stiff posture. Called stays, corsets were made of stiffened fabric with boning in front and back. They laced in back, in front, or at the sides. Court costume was made of high-quality, expensive materials including silks, satins, and taffeta.

Early 18th century hair styles were fairly simple, with hair waved loosely around the face. False ringlets and cushions added volume. Long tresses were drawn up into buns on the crown of the head. Women powdered their hair for formal occasions.

The Mid-1700s

Skirts widened mid-century and court dress took on the excessive styles often associated with the 18th century. In the 1730s, silhouettes narrowed in front and back but widened through the use of panniers, a type of hoop added to each hip.

Pannier (pronounced "pahn-yay") means basket in French. Wicker contraptions attached near the hips added width to skirts creating a swaying effect when women walked, revealing more of the leg than in the past. By 1740, panniers expanded to extreme widths which made it difficult to enter a doorway. Excessive widths drew ridicule from many fronts and caused men to complain that women now took up too much space.. This style remained a staple of court dress until 1760.

Gowns and petticoats became elaborately draped and embellished with ruffles and lace. Open bodices and skirts displayed petticoats and stomachers often made of the same material as the gown so that the costume seemed all one piece.

Stomachers were inverted triangles inserted at the center of an open bodice and held in place with side tabs. Stiff stomachers could be decorated with artificial flowers, ribbons, ruffles, and lace.

Squared or oval necklines were worn low. Sleeves were worn tight to the elbow.

During this time, tight curls resembling sheep's wool and called tete de mouton puffed out on either side of the face. Tight curls were later replaced by sausage curls worn at the sides of the head.

The mantua remained popular and maintained the back pleats that would later be known at Watteau pleats, after the painter who depicted the style in 19th-century portraiture. In the 18th century, the style became known as "robe à la Francaise."

A jacket style called "casaquin" fitted tightly at the bodice but flared out below the waist to accommodate extreme skirt widths.

Madame Pompadour reigned as a fashion icon of the mid 1700s. Mistress of King Louis XV, Mme Pompadour was educated, stylish, and influential, remaining close adviser to the king long after the affair ended. A patron of the arts, Mme Pompadour (shown above) influenced Rococo in the arts, a style that featured soft curves and floral themes.

The robe à la Francaise (1740-1760) featured an open front and panniers.

Amsterdam Museum on wikimedia commons; CC-BY-SA

Late 18th Century

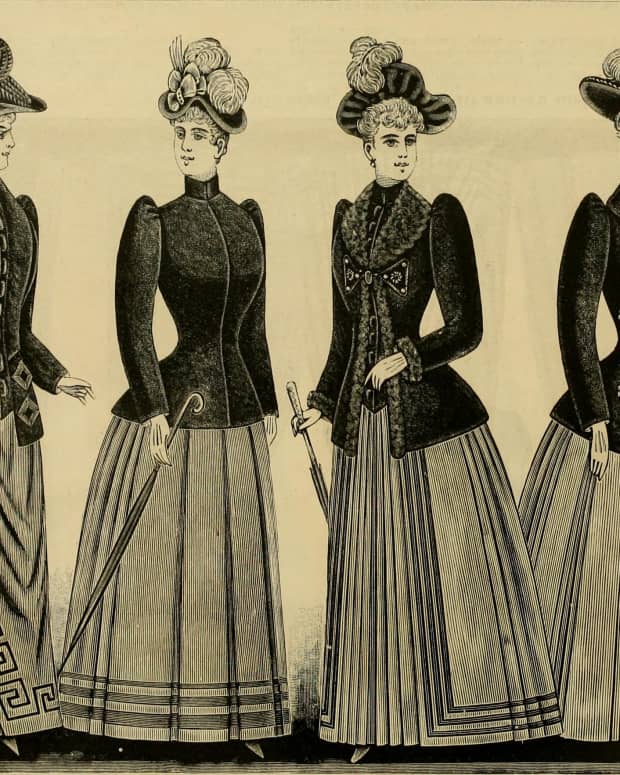

By the late 1760s, panniers gave way to hip pads creating a softer and more natural silhouette. Skirt fabric pulled through slits to form a bunched drape. False, cork-filled rumps, called bustles in the 19th century, emphasized the rear. Hemlines rose to display the leg above the ankle.

The Polonaise style of 1770-1785 reflected a growing interest in folk or pastoral costume. An underskirt was displayed by a separated over skirt that looped and puffed by means of tapes and rings (think Roman shades).

Hair styles rose to great heights in the 1770s. Massive hairdos decorated with feathers, jeweled combs, ribbons, artificial flowers, fake birds, fruit, and other objects rose in complex structures. Hair could be pulled up over wire framing. False hair pieces added to the volume. Tiny hats often perched at the top of this elaborate style.

A growing interest in a more egalitarian society and economy reduced interest in excessive garment and hair styles. English fashions that reflected sobriety encouraged the style-conscious to emphasize propriety and responsibility. As this new Anglomania swept Europe, more women wore the robe a la' Anglaise, a garment with a somewhat fuller bodice fitted close to the waist in front and back that featured wrist length sleeves. Round gowns were worn close fronted to the hem.

Oddly enough, the much hated Marie Antoinette influenced fashion trends long after her execution. While spending time playing at being a simple country woman in a small chateau on the grounds of Versailles, Marie Antoinette wore muslin gowns made of imported fabric. The resulting penchant for imported fabrics devalued the French textile trade but laid the groundwork for 1790s styles. Her gambling, extravagant spending, and close association with her home country of Austria angered a population that suffered a poor economy and food shortages.

The late 18th century ushered in a neoclassical style based on Ancient Greek and Roman design. Light muslin gowns replaced layers of ornate finery. Where once Marie Antoinette was accused of indecency for wearing garments that resembled underwear (i.e. the chemise), those same styles became the norm. Corsets softened along with the new silhouette.

By the 1790s, waistlines rose to just under the bust in a style called Empire. The look lasted into the early 1800s.

Undergarments

The chemise was a thin, full-cut linen or muslin dress with a lace-edged neckline. Worn under everything else, the lace of the chemise could peek out over the edge of low cut necklines. A chemise fell to the knees and featured full sleeves to the elbow.

Petticoats came in a wide variety of styles, weights, and fabrics and often showed as part of the costume, Fabric changed with the seasons, with linen and cotton worn in warmer months, wool flannel in winter. Calico, a good-quality finely printed cotton imported from India, was also used for petticoats.

Stays or corsets made of stiffened fabric helped maintain an erect posture. Whale bone, inserted through slots in the layered material, created more stiffening. Open-style bodices could show a corset, in which case the stays would be covered by the same fabric as the gown, or decorated with ribbons and lace.

Drawers were not yet worn under gowns.

Makeup and Jewelry

French ladies wore heavy lead-based cream as a foundation on the face and decolletage. Extremely pale faces had been in vogue since the Elizabethan era, and suggested that the wearer did not labor outdoors. Heavy makeup also covered wrinkles and blemishes. Obvious blemishes and scars were covered by tiny patches of fabric. These "beauty marks" carried symbolism related to politics and personality. Rouge added bright spots of color to cheeks and lips. Artificially darkened eyebrows were shaped and plucked. False eyebrows made of mouse skin were pasted in place. The extreme makeup style diminished toward the end of the century.

Necklaces could be made of chain or pearls. Pendants and crosses were popular as well. Jeweled hair pins and combs adorned the hair. Rings were not as common as earrings, cameos, pins, and watches. The end of the century saw simpler tastes in jewelry.

Outerwear

Full-cut cloaks could be ankle length, knee length or lip length and were often hooded and featured fur or velvet trim. Calashes were hoods with built-in hoops that created accordian pleats that held the fabric out away from the face.

When large panniers fell out of fashion, men's-wear type coats called redingotes came into vogue.

Large scarves called kerchiefs were worn around the neck. Shawls and wraps were worn indoors and out in cool weather.

Calash-style hood at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY

Downloaded by user PKM; wikimedia commons; PD

Footwear

Stockings made of cotton, wool, or silk rose to the knee and were held in place by tied garters.

Shoes included backless slippers called mules. Dress shoes featured high heels, slightly pointed toes, and tongues with side pieces fastened over the instep.

Clogs or pattens, worn outdoors, in the countryside, or during inclement weather, elevated the foot above the ground.

For Further Reading

Dress in France in the Eighteenth Century by Madeleine Delprerre translated by Caroline Beamish; Yale University Press; New Haven Connecticut; 1997

The Culture of Fashion by Christopher Breward; Manchester University Press; Manchester UK and NY, NY; 1995

The Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion edited by Valerie Steele; Charles Scribner's Sons; NY; 2005

Survey of Historic Costume A History of Western Dress by Phyllis G Tortora and Keith Eubank; Fairchld Publications, Inc; NY; 2005

Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Fashion in Detail by Avril Hart

Eighteenth Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color 64 Engravings From the "Galerie des Modes" 1778 - 1787 by Stella Blum

Costume Close-Up Clothing Construction and Pattern 1750 - 1790 by Linda Baumgarten, John Watson, and Florine Carr

The Dress of the People Everyday Fashion in 18th Century England by John Styles

Questions & Answers

Question: Who were the influential designers from 1700 to 1800?

Answer: Many historic costumes of the 1700s appear in museums without information on the designer.

Marie Jeanne Bertin opened a shop in 1777. The Duchess of Chartres introduced Bertin's designs to Marie Antoinette who brought the designer to Versailles to create gowns for the queen. Bertin exported fashion to European courts including London, Lisbon, and Venice.

A German shoemaker named Effien designed ornate footwear of the day. Bourdon was a French creator of elaborate, bejeweled shoes.

Legros founded the Academy of Hair Dressing, and Leonard Autie, hairdresser to Marie Antoinette, created many of the famous extreme hair designs that rose to nearly four feet in height.

Question: I am in a play and I am trying to dress as accurately as I can to a queen in 1735. Is there anything that would be very important to include in my queen's costume from 1735?

Answer: I think the question is - what would be doable? Royalty of that time period wore very expensive fabrics like silk. Look at fashions of the period to see a beautiful dress that you could actually make. The styles were complicated so that should be something to think about as well. You may not want to be too authentic with materials as the cost would be significant.

May I suggest a book - "Making Georgian and Regency Costumes for Women" by Lindsey Holmes.

© 2017 Dolores Monet

Comments

Lily on August 21, 2019:

Who was the fashion designers of the mid 18th century?

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on April 12, 2019:

Hi Miro - the grand, super fancy outfits portrayed in many painting show garments worn for court or special occasions. Simpler version of the same styles were worn for day wear, walking, and riding. Working people wore simplified versions of the grander styles and were made of cheaper materials. Working women wore aprons to protect their dresses.

The other information you requested is in the article. For more information read one of the books suggested above.

Miro on April 11, 2019:

Hello Dolores, I'm a school student and im school we're writing about clothes so I chose to write about the dresses and gowns of the 1700s. I have some questions that I'd like to ask.

First of all How were the dresses usually built, coursettes? ect.

And also i would like to know, did they always wear these excessive and "over the top" dresses?

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on March 02, 2019:

Hi Kimberly - a type of cloth called jeane, a cotton/wool blend was worn by Italian sailors even before the 1700s. Serge de Nimes was produced in France of cotton. In the late 1700s, denim was produced for working people in the USA. But these were not quite the jeans we know today. Rivets were added in the American West for miners in 1872. Zippers were not invented until the late 1920s.

Sandals as we know them were not used by fashionable people in the 1700s as too much of the foot was exposed.

Girls dressed in modified styles that women wore. In portraits they almost look like miniature adults, but that was for special occasions. Day wear for girls would be somewhat more comfortable and were not worn with corsets.

Kimberly on March 01, 2019:

Did women wear sandals back in the 1700s? What did girls wear back then in the 1700s? Was there a such thing as jeans in the late Seventeen Hundreds?

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on April 09, 2018:

Hi Liv - casual clothing worn around the home would be simple with no wide panniers and less embellishment.

Peasant women wore shorter skirts, above the ankles. Fabrics for peasant wear were coarse weave linen, occasionally cotton (prints), and wool. Natural colors were easier to manage and cheaper to purchase than most bright colors. The color blue, for instance, made of woad washed out and faded. Linen for the common folk was ecru or natural linen color. Yellow was an easily found and afforded dye. Rust, subtle pink, and off shades of red were common. Women wore head covering, a coif with a scarf, or wide brimmed hat. Aprons and smocks protected clothing. Clogs kept feet dry.

You can find images of peasant costume on Google images. So many are very attractive. Mixing prints was popular. Of course how peasants and working people dressed varied greatly by country.

liv on April 07, 2018:

what sort of things did people wear casually back then? What kind of things were the peasants into?

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on October 11, 2017:

Hi Natalie - my fashion articles are a general overview about styles worn by the elite. If you are going to write historic fiction, I would recommend reading several books on the subject including general history as well as costume history. I would like to address clothing that regular people wore but more images of the elite are available. Thanks!

Natalie Frank from Chicago, IL on October 10, 2017:

Great article! I have been doing a little of writing lately set in different time periods.and have gotten caught up in the research (what did we ever do before Google?) This article is very interesting and will be suite useful for a piece I'm writing. Thanks also for thwhen follow. I hope to see your comments on some of my artocles.

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on October 03, 2017:

Hi Dora - while they may have endured extreme discomfort in order to look good at ceremonial occasions, I can't actually admire them. France, at the time, was in economic duress. The elite partied on and lived lavishly despite the struggles of regular people leading to a bloody revolution. It did not work out well for the aristocracy! Thanks!

Dora Weithers from The Caribbean on September 29, 2017:

I admire the women of the era you describe for their commitment to tradition and culture. They stood for something despite the cost and the discomfort. I also admire today's women who mange to combine standard with comfort. I like your fashion posts. Thank you.

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on September 29, 2017:

Hi Nicole - the featured costumes were not for comfort but intended to display social status. Regular folks may have attempted to imitate the looks to some extent, but common people dressed in a more sensible manner. They had to in order to work. "Undress" signified much more comfortable garments worn at home.

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on September 29, 2017:

Hi Doug - they weren't much on hair washing in those days. I am going to add a bit more info to the makeup section. It's so hard to keep this from running too long. Small patches similar to what was later called "beauty marks" could hide scars too. Pale faces indicated that the wearer was noble and did not work outdoors.

Kitty Fields from Summerland on September 29, 2017:

Dolores - I always enjoy your historical fashion posts. I'm a big history buff, and I went to school for fashion design...so these are right up my alley! That being said, I don't know how these women were ever comfortable or cool. LOL

Doug West from Missouri on September 28, 2017:

From what I have read, the wigs on men where because they didn't have hair or they hadn't washed it in a while (a long while) and the face paint was to cover their small pox scares. Sound right?