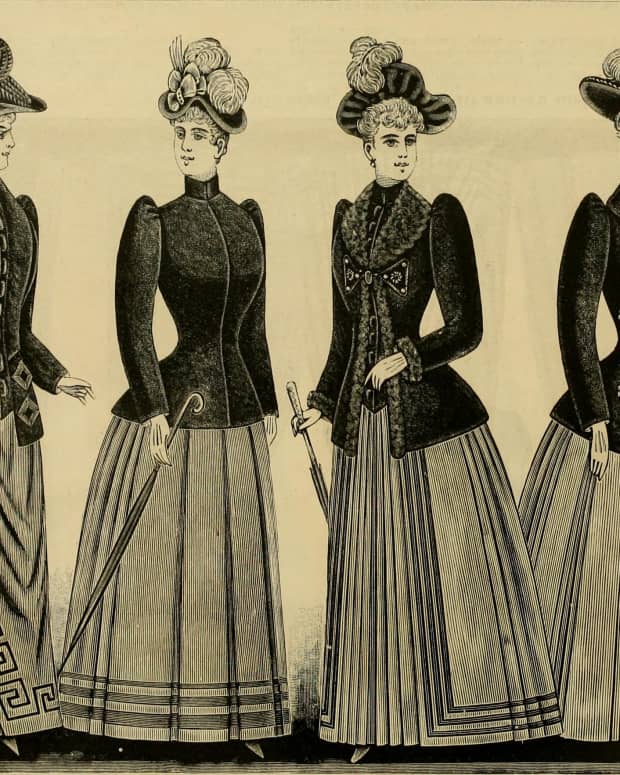

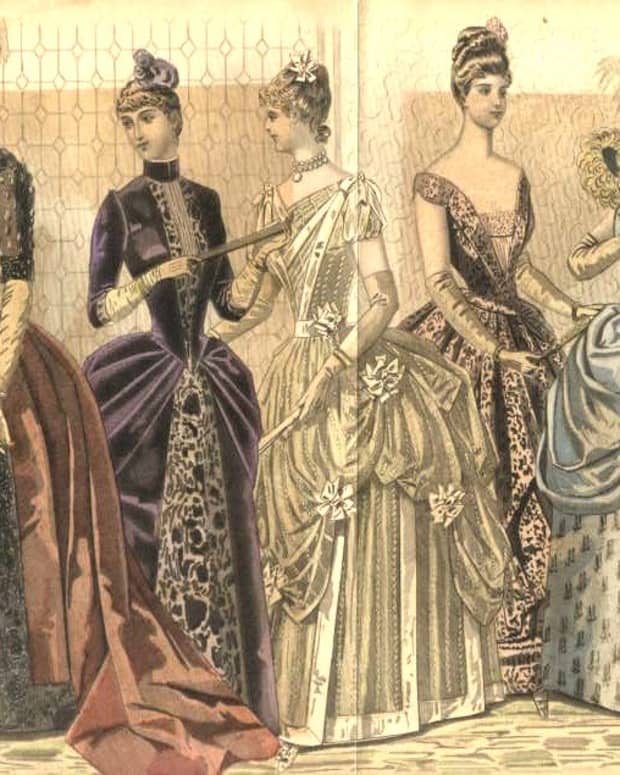

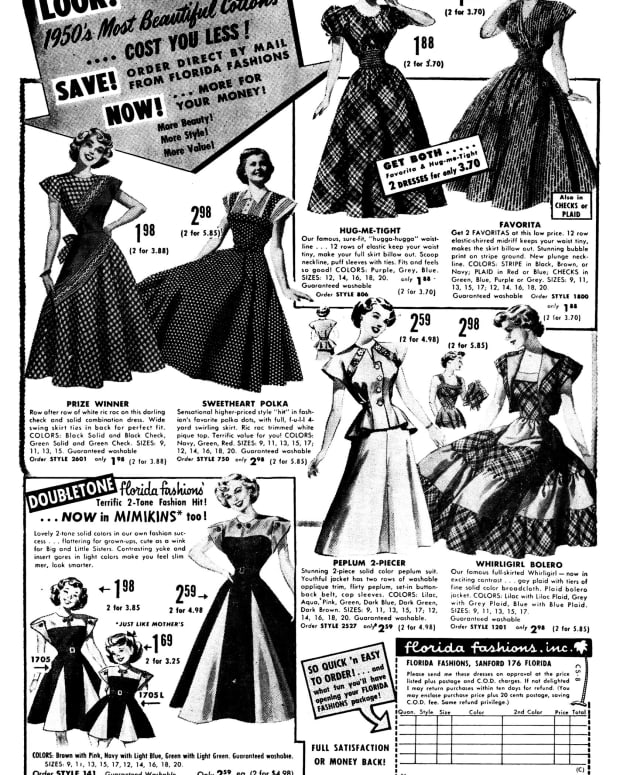

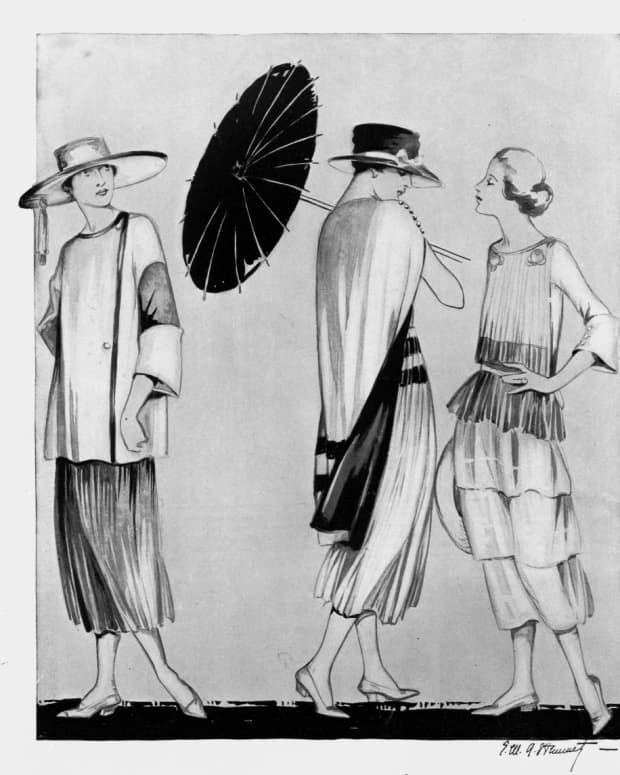

Women's Fashions of the 1600s

Dolores's interest in fashion history dates from her teenage years when vintage apparel was widely available in thrift stores.

Women's clothing of the 17th century followed the Baroque style of the time. Highly ornamental Baroque fashion featured soft, free-flowing lines and a release from the stiff, structured garments of the Elizabethan Era. While French fashion, influenced by King Louis XIV, was highly elaborate, the styles of Protestant countries were more subdued.

As in the previous century, women wore many layers of clothing. Europe was going through a cool climate period known as the Mini Ice Age. While not exactly an ice age, though glaciers did advance, wearing many layers made sense.

Fabrics and style influences from Asia became more available due to an expansion of the shipping trade. While overland routes had previously enabled East/West trade, shipping greatly increased commerce with the import of Chinese silk and Indian cotton. The British East India Company, founded in 1600, took control of portions of India, granted the right by King Charles II to coin money and command troops in the region.

Consumer demand for imports, including inexpensive Indian cotton, became acknowledged as an important part of the economy. Fashion was recognized as a commercial entity, reported on in magazines. The French periodical Le Mercure Galant, a society magazine produced from 1672–1674 and in 1678 Donneau de Vise, offered articles on life at court, theater, political opinion, and fashion. Illustrations of fashionable garments by printmakers Jacques Callot and Abraham Bosse were accompanied by details on fabrics, shoes, and accessories as well as mentions of suppliers and merchants.

Fashion dolls passed around at court displayed new fabrics and styles for inspiration.

As in the previous century, the elite set fashion trends. Louis XIV dictated the types of garments, fabrics, and styles worn at court. He even regulated the length of trains on ladies' gowns with higher status women allowed to wear longer trains.

Historical information about clothing worn by the elite and upper-middle-class comes from fashion drawings, paintings, written records of laws, merchant's inventories, and household accounts. The written word is more reliable as paintings could feature out of date, or fanciful clothing. Few intact garments of the period are available today as fine clothing was taken apart and remade.

Linen jacket with narrow sleeves embroidered with silk

Victoria and Albert Museum on wikimedia commons circa 1610

Early 1600s

While the architectural styles of the Elizabethan Era persisted early on, the farthingale (a wide, hooped skirt) disappeared by 1613. Women's clothing became more natural with soft, flowing lines. Necklines could be high or low and rounded.

The stomacher (a stiff V-shaped piece inserted at the front of the bodice) lengthened into a U shape. The stomacher could match or contrast with a bodice or gown changing its look and adding variety to a woman's wardrobe. Embroidered linen with silk thread featuring flowers and scrolling vines was a popular motif.

The sides of gowns and skirts were wide and full. Sleeves were capped with small wings at the shoulder. Early in the century, sleeves were tight but puffed in the 1620s and '30s. Virago sleeves were puffed and gathered with bands.

Ruffs, wide wired or starched collars grew in size in the Netherlands but became smaller in France.

The white linen chemise continued as an essential undergarment and continued for many years.

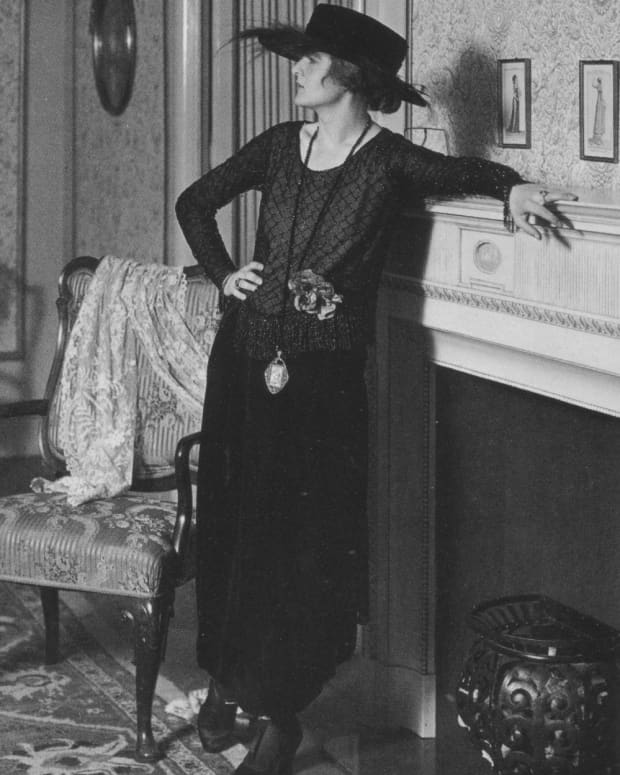

For a short time, early in the century, some young women took to wearing masculine attire, including doublets and wide-brimmed black hats.

1630 satin high waisted gown. Woman's hair with short curls in front.

Wikimedia commons; public domain

1630–1660

Bodice and skirts were seamed together at the waist. The waistline rose, and gowns were worn open at the center front, showing off underskirts. The outer gown was worn over an underbodice, which was boned and stiffened like a corset.

The open gown showed off beautiful underskirts with the outer skirt sometimes worn hooked up over the arms. Even when the outer skirt (the modeste) was worn closed in front, an underskirt (the secret) was also worn.

Bodices featured extensions that fell below the waist. Low cut necklines were softened by linen kerchiefs or nearly transparent collars. The ruff collapsed into a wide, falling collar gathered at the neck, sloping towards the shoulder. Laced front bodices were covered by a deep, pointed stomacher.

Read More From Bellatory

Hair was parted at the ear from side to side and pulled back into a roll with the front arranged in tight or frizzed curls.

Coifs and small linen caps, were worn indoors and out, though some women went bareheaded. Women wore wide-brimmed cavalier style hats. The capotain was a hat worn over a coif that featured a high crown and narrow brim. By 1635, the brims narrowed, and hat bands were decorated with feathers. Hoods were worn outdoors along with capes.

Tiny patches applied to the face appeared in a variety of shapes, including stars, hearts, circles, and crescents in a style that persisted for eighty years.

Woman in black dress with stomacher, falling collar, and elbow length sleeves cira 1665

Painted by Van der Helst; wikimedia commons; public domain

1660–1680

The silhouette changed as bodices lengthened and narrowed in a style that slenderized the figure. Stomachers extended to a long V in the front. Necklines were low and wide, horizontal or oval. Falling collars fell out of fashion by the 1670s, although the kerchief was worn outdoors, covering the neck area to the shoulders.

Sleeves set low on the shoulder were puffed or ruffled, ending just below the elbow. Skirts were worn either open at the front or closed. Open overskirts draped back at the hip line. Gowns featured rows of ruffles down the front. Seam construction lines were decorated with lines of ribbon or braiding.

Women's fashion continued to become looser with an air of calculated disregard.

1680–1700

A new style emerged in clothing construction for women's garments. Rather than cutting the bodice and skirt separately, then sewing them together, gowns were now cut from shoulder to hem. The style called "mantua" was inspired by the clothing of the Middle East.

A mantua was fuller than the old style but could be belted for a neat fit. A loose mantua was a comfortable garment to wear at home. Pleated versions that featured pleats in front and back made for a dressier, more traditional look. As with skirts of earlier years, the front skirt area could be draped back. Underskirts featured decorative elements like embroidery, ruffles, and pleating. Heavy, layered overskirts were supported by whalebone, thin metal, or with basketwork.

Hairstyles were high on top of the head with long, curling locks at the sides and back. The fontage became a popular headdress. Wire supported layers of ruffles and lace on top of the head. Though small at first, the fontage grew in height, eventually featuring three to four tiers of lace in front with lace, ruffles, and bows falling down the back.

Necklines rose and squared with the decorative edges of the corset visible. Some necklines were perfectly horizontal. Women continued to wear stomachers that were tied or pinned to the front of the bodice. Embroidered stomachers changed the look of an outfit.

Fabrics of the 1600s

Linen and wool continued as wardrobe staples. Linen was worn by nearly everyone with finer weaves and brighter whites worn by the elite. The lower classes wore coarse woven linen in natural hues like beige or gray. Linen, being easy to clean, was worn close to the body and for summer.

Hemp was a tough, durable, coarsely woven fabric worn by the poorest people. As fabric was woven and made at home, hemp was easier to produce than labor-intensive linen.

Lower class people wore wool outer garments, including dresses, skirts, and cloaks. Wool has the unique quality of keeping the wearer warm even when it's wet.

Cotton became a popular new fabric choice. Imported Indian cotton was inexpensive and easy to clean. Muslin is a fine, lightweight cotton that is soft and durable.

Chintz was a hand-painted or printed cotton fabric. Today, we think of chintz with a glazed surface, but not all chintz was glazed in the 17th century. European merchants provided Indian manufacturers with European style patterns. Asian themed patterns were popular as well. Artichokes and pomegranates were popular design motifs. At first, chintz was used for bed linens, curtains, and tablecloths. By the late 1600s, it became widely used for garments. At the time, European printed fabrics were not color-fast, but chintz designs did not fade in the laundry.

Velvet came in a variety of styles and thicknesses. It could feature stamped designs or woven-in metallic thread. The finest velvet was patterned silk velvet.

Silk was very expensive and worn by the elite. Heavy satins were worn for formal occasions and often show up in portraiture. Pastels and bold colors were popular in solid colors.

The garments worn by the upper class were made of bright colors due to the expense of dyes. Portraits often show women wearing black, which was the most expensive dye, so reflected the status of the subject. The natural dyes of the common folks came in muted tones and faded with washing.

Clothing of Lower Class Women in the 17th Century

Lower class women wore styles similar to the elite but made of cheaper fabric with less complicated tailoring and decoration. Women of the lower classes made their own garments, wore hand-me-downs, or purchased used clothing. High-quality dresses, table cloths, or curtains could be deconstructed and made into new garments.

Domestic servants usually dressed well. They were offered their employers used garments and linens. The use of used chintz tablecloths and curtains for clothing was an early instance of a fashion trend moving up from the lower classes into the elite.

Working women wore ankle-length skirts for ease of movement and to keep their hemlines clean. Bodices were laced in front and usually worn without a stomacher.

Women wore aprons to protect their garments at home. Some of the aprons during that time could be quite pretty with ruffles and embroidery.

Women's Footwear of the 17th Century

Women wore pumps with somewhat pointed toes and chunky high heels. The heels grew higher and narrowed in the last third of the century. Made of embellished leather or brocade, shoes tied closed with a ribbon at the top.

Pantofiles were heelless slip-on shoes with cork soles usually worn at home.

A wooden platform could be attached to a shoe for outdoor walking in the filthy streets. They raised the foot up from the ground. Called chopines and covered with velvet and embellished with beads they became very tall and a topic of ridicule by some critics.

By 1640, high heels developed a slight curve at the back of the heel. Squared toes came into vogue. By the 1660s, heels grew higher and the shoe slimmer at the front. Between 1660 and '70 an obvious white line showed where the upper part of the shoe met the sole. By the 1690s, curved heels came back into style.

Accessories of the 17th Century

Accessories included gloves, handkerchiefs, purses, fans, fuffs, and muffs. Face masks were sometimes worn in bad weather to protect the skin.

Women wore necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and rings. Pomander balls were made of filigreed silver or gold and held balls of perfumed resins coated with cinnamon, cloves, and musk oil. They often hung like a pendant.

Nosegays, small bouquets of herbs and flowers were carried and held up to the nose to mask the stench of open sewers.

Short strings of pearls were popular for most of the century and can be seen in many portraits.

Muffs, worn in winter for warmth were convenient for tucking in money or handkerchiefs.

Women continued to wear a coif, a small linen cap. The fontage was a lace headdress based on a mantilla.

For Further Reading

The Cut of Women's Clothes 1600–1930 by Norah Waugh

Patterns and Fashion 1 : Englishwomen's Dresses and Their Construction 1660–1860 by Janet Arnold

A Visual History of Costume in the 17th Century by Valerie Cummings

Handbook of English Costume in the 17th Century by C. W. Cunningham and P. Cunningham

Clothing of Provincial England by Danae Tankard (ebook)

What People Wore When: A Complete Illustrated History of Costume From Ancient Times to the 19th Century for Every Level of Society by Melissa Leventon

© 2020 Dolores Monet

Comments

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on October 02, 2020:

Hi Peggy - I love to look at the old art but we have to be careful when looking at clothing. Many artists choose to depict subject in clothing of the past.

Peggy Woods from Houston, Texas on September 25, 2020:

Your articles about fashion are filled with not only information about the period, but fantastic illustrations as well. Artists during each period were often paid to paint royalty and wealthy people. Because of it, we can easily look back at fashions through the ages when visiting museums. Your tidbits of information are always so interesting. Thanks for documenting the women's fashions of the 1600s.

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on August 09, 2020:

Hi Maren - stomachers provided women a way to create variety in her wardrobe. Different stomachers could change the look of an outfit. One bodice or gown could be worn with a matching, contrasting, or highly embroidered stomacher for different looks. In the late 1600s, they fit in a manner that uplifted the bosom where earlier they flattened the chest. They were a fashionable accessory, not a means of achieving modesty. Thanks!

Maren Elizabeth Morgan from Pennsylvania on August 08, 2020:

Fascinating article. Did stomachers evolve to provide modesty for ladies? I ask because the Amish and Old Order Mennonites in my area wear a dress style with an extra rectangle of fabric over their chest and down to the waistline. It serves no practical purpose - just hides a woman's bosom.