The Victorian Beard Craze

I've spent half a century (yikes) writing for radio and print—mostly print. I hope to be still tapping the keys as I take my last breath.

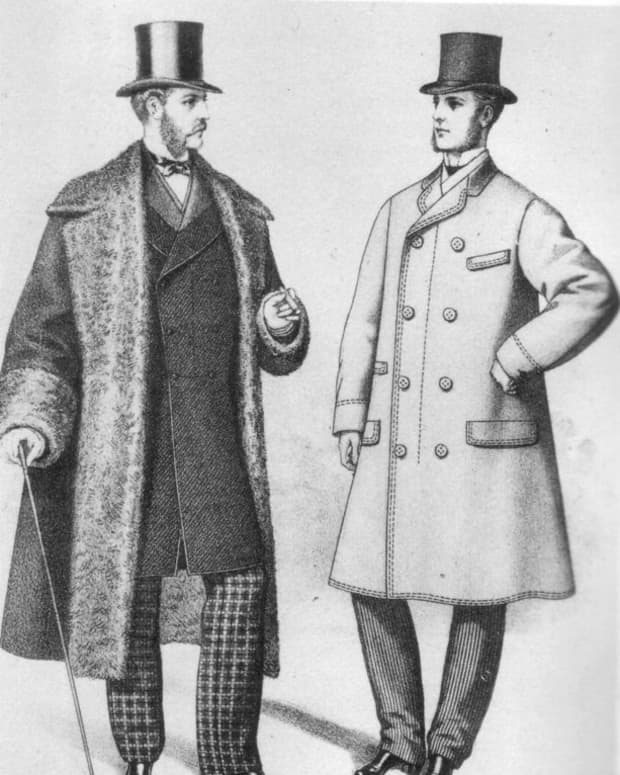

Beards are back. We’ve gone from designer stubble at the end of the 20th century to full beards in the 21st. Will we progress/regress (matter of opinion) to the exaggerated hirsute look of the 19th century?

Beards Signified Courage

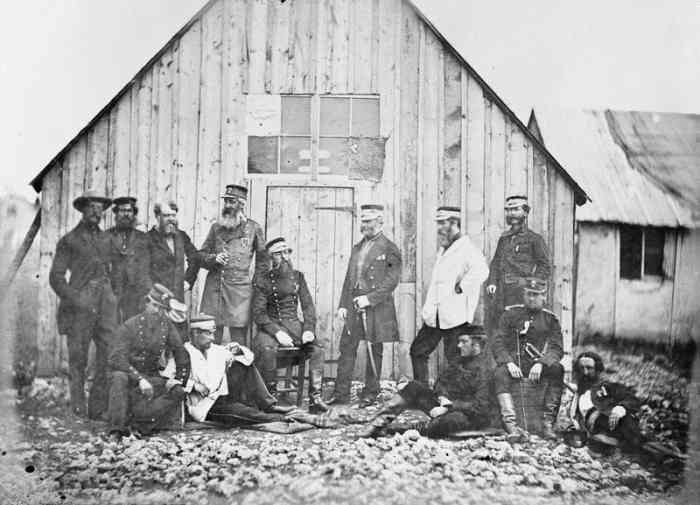

About the middle of the 19th century, men in England began sporting extravagant facial hair. The change from the clean shaven look came about as a result of the Crimean War.

The ill-advised conflict that started in 1853, pitted Britain and its allies against Russia. It was fought, in large part, on the Crimean Peninsular, a place that experiences harshly cold winters.

For many years, the British Army had a ban on beards but, when the frosty nights arrived, the military displayed a previously undetected willingness to adapt to changing conditions. Beards were now encouraged as a way of offering a bit of insulation against frostbite.

After the usual catalogue of military blunders whose effects were born mostly by the grunt soldiers, the war ended in 1856. When the surviving soldiers returned home, they kept their beards and moustaches as badges of honour.

Then, other men who had never been near a battlefield started growing facial hair. Writer Lucinda Hawksley notes that “Within a few years, it was almost impossible to see a beard-free male face in Victorian Britain.”

Crisis of Masculinity

There’s another view of why beards became popular in the Victorian era, not entirely separate from the previous one. The idea developed that the British male had grown soft and flabby through idleness. This, of course, applied only to the small leisure class that did not have to endure sweat labour to feed their families.

So, the copious whiskers took on the aura of manliness. Advocates of the unshaven look leaned on a Renaissance theory that a beard was a sign of “a fire burning below” i.e. male potency.

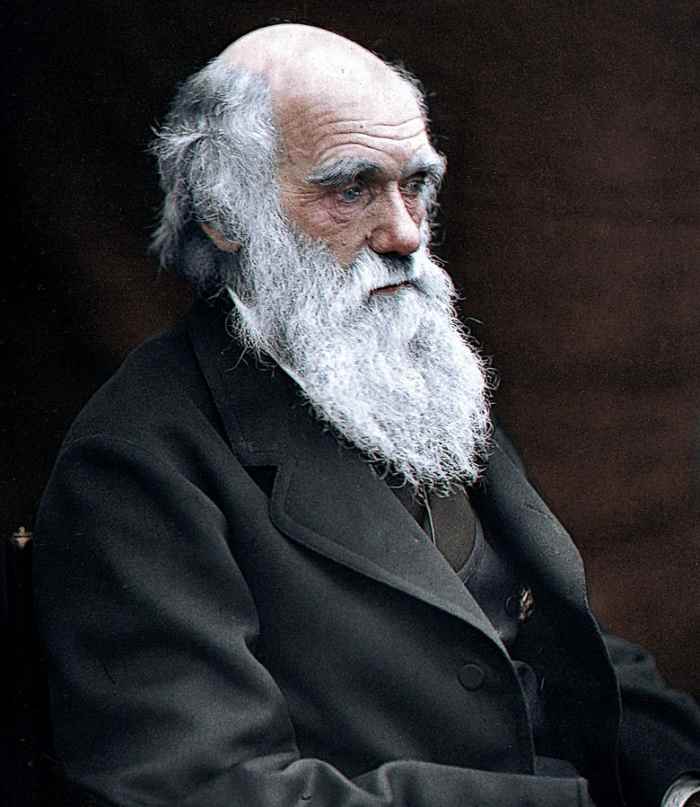

A magazine call The Crayon noted in 1859 that age and a beard denoted gravitas: “When half a hundred winters have blown their snows and sleets upon it, how venerable does the patriarch look?”

There's another theory that the first stirrings of the movement for the empowerment of women were having an impact on gender roles. Men were feeling threatened. A lavish display of facial hair was a statement masculine power.

For those unfortunate men whose ability to sprout flamboyant whiskers was limited, help was available. Charlatans peddled useless creams and unguents with claims that abundant hair growth would result. More practical, but probably quite easy to spot, were fake beards and moustaches sometimes made from goat hair.

A London wig maker obtained a patent for a contraption “with fastenings made of a certain elastic compressed steel or springs, and also with other flat springs or wires made of steel, for the closer adhesion of the points and whiskers to the head and face.”

Charles Dickens developed a style known as the “doorknocker beard.” He wrote an essay entitled Why Shave?

Beards and Health

Supporters of the fashion cast about for evidence that their idea was valid. The Scottish physician Dr. Mercer Adams offered his opinion that facial hair was the “badge of manly strength and beauty.” He added that “hair covering the jaws and throat is intended to afford warmth and protection to the delicate structures in the vicinity, especially the fauces (opening at the back of the mouth) and the larynx.”

The hairy growth was called “nature’s respirator” that stopped germs, dust, and noxious substances from getting into the lungs. A government committee charged with improving workplaces suggested that workers “who are exposed to the influence of dust, grit, chips, splinters &c,” should grow beards.

The Workman’s Times was a pro-labour newspaper. It carried a story about an anonymous “medical writer” who examined a clean-shaven face through a microscope. And, horrors, he “discovered that the chin resembled a piece of raw beef.”

Read More From Bellatory

There were even claims that beards cured toothache by keeping cold air from getting at that abscessed molar. They were also believed in some circles to aid eyesight because of the observed connection between pulling out beard hair and the consequent watering of the eyes. Clergymen and other public speakers were advised that beards protected the vocal chords.

Medical science still had a way to go.

Beard Popularity in America

The craze for whiskers crossed the Atlantic Ocean through the agency of European fashion magazines.

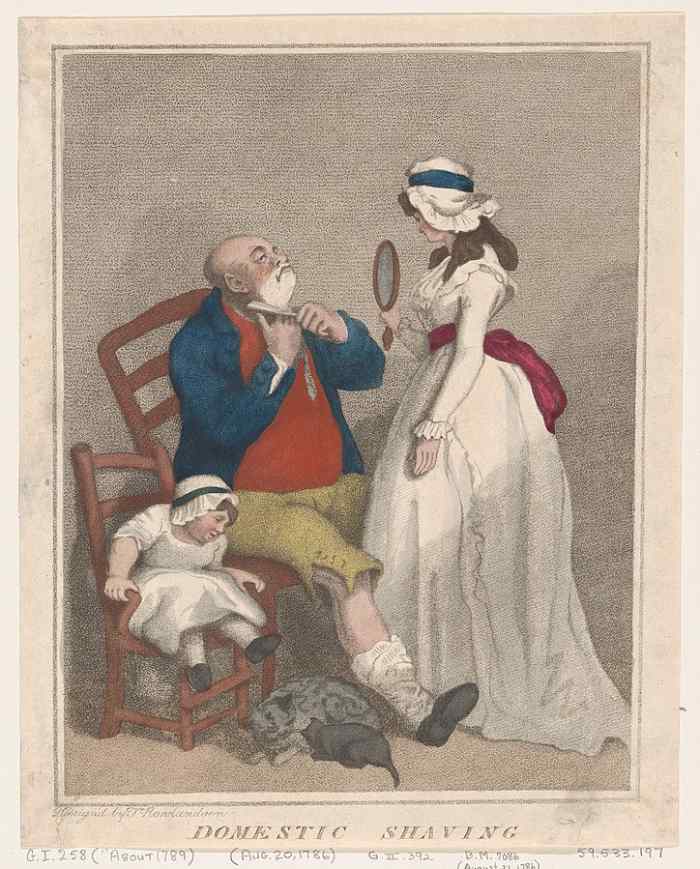

However, historian Sean Trainor contends American men adopted the beard as a way of avoiding “the painfulness of their morning toilet.” The straight razor could inflict fearsome damage to the face of the distracted or inexperienced shaver. The bloodletting could be dodged by simply letting the hair grow.

So, when hairiness was given the seal of approval by Europe’s fashion gurus, American men latched onto it with enthusiasm.

In 1856, Boston’s Daily Evening Transcript published a 21-part series of articles in praise of the beard. Sean Trainor notes that the newspaper “argued that the beard represented a rugged and robust ideal of manhood, proving white Americans’ dominion over ‘lesser’ men and ‘inferior’ races. The pseudonymous ‘Lynn Bard,’ for instance, claimed that men took up shaving ‘when they began to be effeminate, or when they became slaves.’ ”

Historian Sarah Gold McBride agrees. She has written that the bewhiskered look was a response to the growing movement for women’s rights. She says men grew beards “to codify a distinctly male appearance when other traditional markers of masculinity were no longer stable or certain.”

Hans Langseth was a Norwegian-American whose beard when he died in 1927 measured 5.33 metres (17.5 ft).

Decline of Beards

The popularity of ebullient facial hair continued until the end of the Victorian era. The invention of the disposable safety razor in the late 19th century banished the fearsome reputation of the straight razor, sometimes called with gallows humour the “cut throat razor.”

Another factor in the decline of beards was what prompted their popularity in the first place―war. Soldiers in the two world wars found that the gas masks they were issued didn’t seal well against a hairy face.

The clean-shaven look prevailed until the current fad reached what some observers called “peak beard” around 2013.

Bonus Factoids

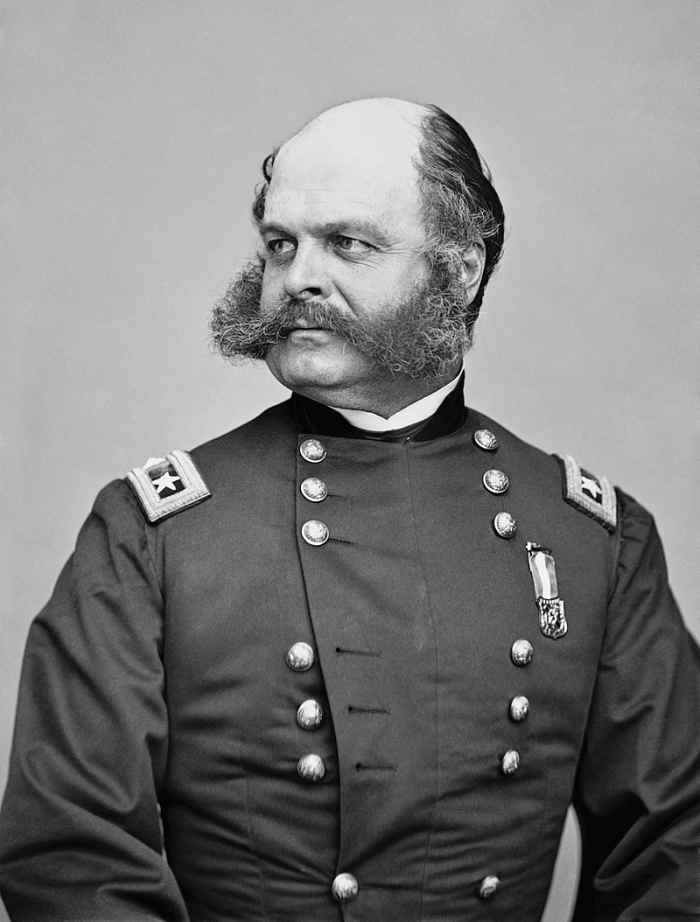

- Major General Ambrose Burnside (below) was a Union Army leader during the Civil War. He developed a bushy moustache that joined up with his side whiskers. His name was twisted to call the style “sideburns.”

- John Thoreau was the brother of Henry David Thoreau. In January 1842, he was sharpening his straight razor when he cut his finger. This resulted in tetanus and death from lockjaw within a few days. He was 26 years old.

- The play Our American Cousin opened in London in 1861. In it, a character named Lord Dundreary had exuberant side whiskers that became known as “dundrearies.” It was this play that Abraham Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated.

- The British Medical Journal warned of the cost of shaving in 1861. The august publication calculated that the time spent shaving in America each year cost the economy 36 million working days.

- Hans Steiniger, the mayor of Braunau, Austria, possessed a very long beard that he kept wrapped around his waist. In 1567, a fire ravaged the town and the mayor, running to escape the flames, tripped on his unravelled beard and broke his neck.

- Somebody who studies or admires beards is called a pogonophile.

Sources

- “The Great Victorian Beard Craze.” Lucinda Hawksley, BBC, November 17, 2014.

- “Beards, Masculinity and History.” Dr. Alun Withey, Wordpress, December 23, 2015.

- “A Brief History of Beards.” Dr. Alun Withey, BBC History Extra, May 21, 2018.

- “Power Is on the Side of the Beard.” Sarah Gold McBride, U.S. History Scene, undated.

- “The Racially Fraught History of the American Beard.” Sean Trainor, The Atlantic, January 20, 2014.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2021 Rupert Taylor