The History of Top Hats

I've spent half a century (yikes) writing for radio and print—mostly print. I hope to be still tapping the keys as I take my last breath.

The Origin of the Top Hat

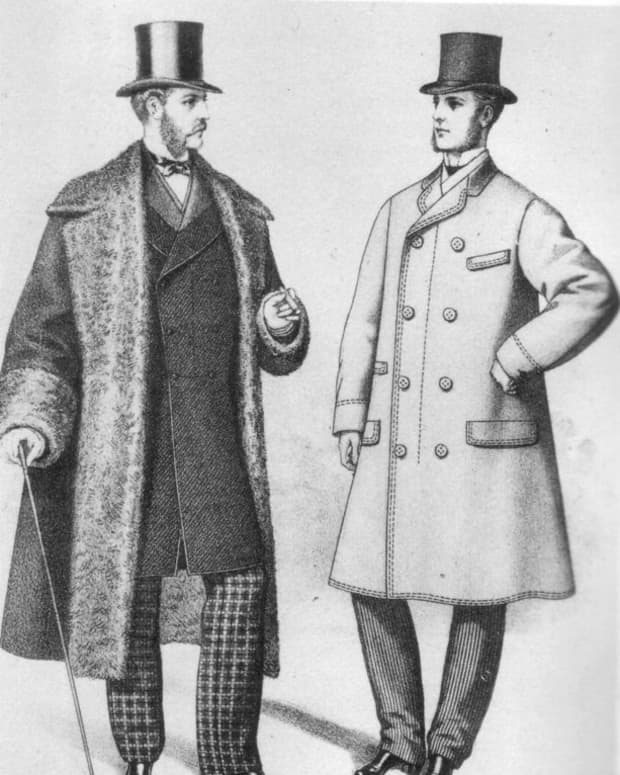

Now used mostly only by aristocrats, people in dressage competitions, and magicians to produce concealed rabbits, the top hat was once an essential adornment among influential people and those who thought themselves important.

As with many fashion items, the day the top hat first saw the light of day is difficult to pin down. One origin is based on a story of doubtful authenticity that involved a haberdasher named John Hetherington stepping out onto the streets of London wearing a topper.

The narrative is attributed to both The Times and St. James's Gazette and has Hetherington surrounded by a crowd in awe of the "tall structure having a shining lustre, and calculated to frighten timid people" (The Times, allegedly). The story continues that, after a riot, charges were laid against Hetherington for breach of the peace.

It's more likely the top hat evolved from the sugarloaf, or capotain, hat that was popular headgear for women and men in the late 16th to mid-17th centuries. And, it's also likely that the bragging rights for inventing the chapeau in question was a man named George Dunnage, who turned one out of his hatter's shop in 1793.

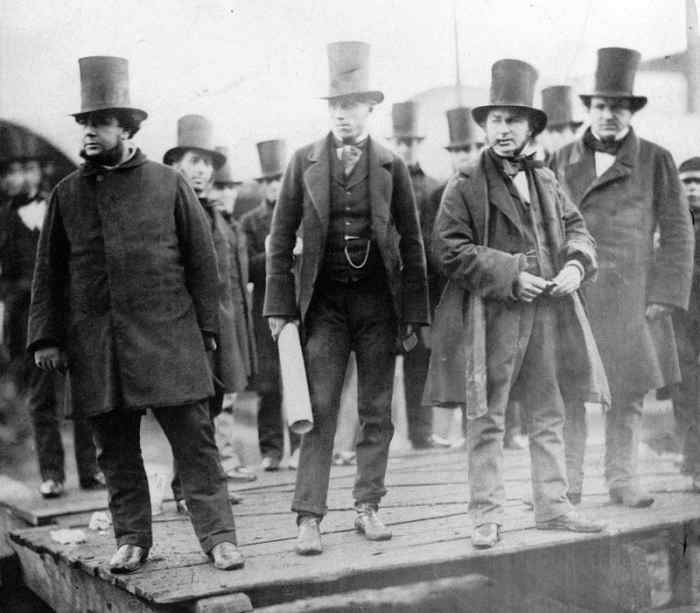

By the early 19th century, the top hat had become the hat of choice for society gentlemen. It carried the stamp of approval from none other than George "Beau" Brummel, the fashion dandy and arbiter of good taste; if Beau Brummel wore a top hat, everybody had to wear it. The top hat became ubiquitous throughout the western world.

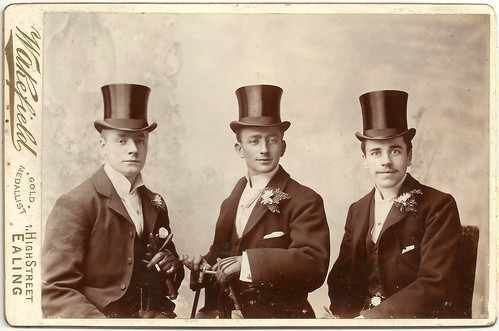

The great British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel (second from right) and companions wearing the top hat style known as the “stovepipe.”

The Making of a Top Hat

The beavers were tasked with donating their lives and fur, no doubt unwillingly, to manufacture high hats. The animal's pelt was felted in a process that was extremely hazardous to the hatters doing it.

The fur was separated from the skin, matted together, and subjected to a process called "carroting." The fur was pressed and shrunk using steam and mercuric nitrate. The felt was then shaped into the desired conical form and stiffened with glue.

The process gave off mercury vapour that was breathed in by the hatters, causing mercury poisoning.

Medicinenet.com tells us mercury poisoning can cause a host of unpleasant things to happen, such as "Tremors, emotional changes, insomnia, weakness, and muscle atrophy . . ."

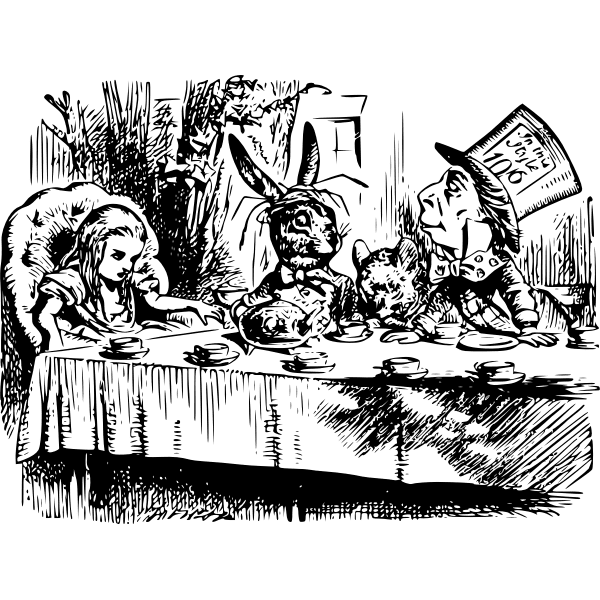

Another noticeable symptom is a decline in cognitive function, giving rise to the phrase "mad as a hatter."

Lewis Carroll used the infirmities of hat makers in his Alice in Wonderland character The Mad Hatter.

Silk Top Hats

During the 1830s, a huge sigh of relief passed in the beaver community as the silk top hat hit the market. The new hats were made on a frame of cheesecloth, flannel, and linen made rigid by shellac. Then, they were covered by black silk.

Brims got wider, and then they were made narrower; some hats became tapered while others had a lower crown. Then, they got taller, reaching 12 inches or more. This created an entirely new occupation, the theatre hatter-checker, so gentlemen could leave their headgear and not obstruct the view of audience members.

But, the Frenchman Antoine Gibus ruined that line of work by inventing the spring-loaded opera hat that squashed down to an inch or so in height.

Today, top hats are essentially back to being made of felt, with the grey version becoming more popular for slightly less formal occasions. Woe betide the man who turns up at a very formal event in a grey topper; such a bounder might well be asked to resign from his club.

The Decline of the Top Hat

By the start of the 20th century, the topper began to be pushed aside by the bowler hat, fedora, and boater. As fashion lecturer, Alice Payne notes in The Conversation, “The top hat became associated with Victorian stuffiness and formality, and was pulled out only for strictly formal occasions: weddings, the opera, garden parties, Ascot.”

Read More From Bellatory

Top hats are also required headgear on February 2 every year when Shubenacadie Sam, Wiarton Willie, Punxsutawney Phil, and all the other weather-forecasting groundhogs are dragged out of their burrows to predict the onset of spring.

The topper held on in a few bastions of privilege. In the rigidly formal world of diplomacy, top hats were required during official ceremonies. All the Japanese delegates to the signing of the surrender at the end of World War II incongruously wore top hats. John F. Kennedy was the last American President to wear a topper at his inauguration.

The Top Hat in Popular Culture

Wilkins Micawber is the optimistic but often bungling character in Charles Dickens' novel David Copperfield who is always confident that something will turn up. He is always portrayed wearing a top hat and was modeled by Dickens's father, who also found himself in debtor's prison.

The Micawber character inspired an early British comic strip about a lazy, top-hatted schemer named Ally Sloper.

Moving right along, Ally Sloper reappeared in 1915 in the persona of W.C. Fields's onstage performances as the boozy swindler looking to make a dishonest dollar. Fields, of course, wore a top hat, tails and carried a cane. In the 1930 film version of David Copperfield, who should play Mr. Micawber? W.C. Fields, of course.

Satirists have loved the top hat as a symbol of wealth and privilege—think Monopoly's Rich Uncle Pennybags, Disney's Scrooge McDuck. Whenever there is a need for an image to depict capitalism, the trusty top hat is called upon.

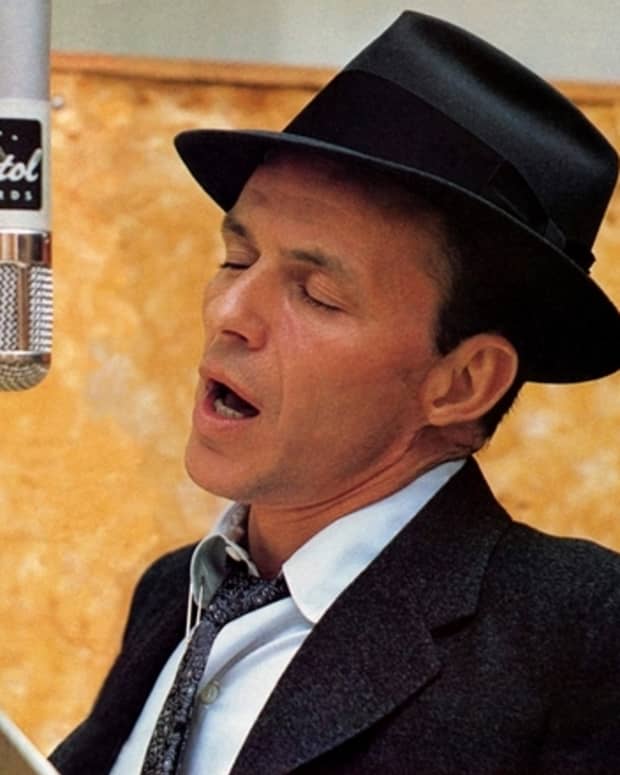

Many entertainers have used the top hat as a prop, from Marlene Dietrich's 1930 movie Morocco to Slash, the one-time lead guitarist with Guns N' Roses. And, perhaps, one of the last times a topper was used without irony was in the eponymous movie Top Hat.

Bonus Factoids

- According to Quirky Science, urine was frequently used in making felt because it is nitrogen-rich. Hat makers sometimes used their own urine if the pee donor was being treated for syphilis. The standard therapy for that disease in the 19th century was to dose the patient with mercurous chloride some of which would make it way into the urine and aid in the felting process.

- Reacting to change with bewildering speed, Britain's House of Commons ceased the daily use of top hats. That was in 1998.

Sources

- “Did the Mad Hatter Have Mercury Poisoning?” H.A. Waldron, British Medical Journal, December 24, 1961.

- “Mercury Poisoning Definition and Facts.” John H. Cunha, medicinenet.com, December 10, 2019.

- “The Story of … the Top Hat, Alice Payne, The Conversation, May 7, 2014.

- “The Top Hat: Its History and Popularity.” Geri Walton, April 10, 2014.

- “Top Hat: An Intriguing History of the Topper.” The Field, June 6, 2017.

- “Mad Hatters, Felt, and Mercury.” quirkyscience.com, June 11, 2012.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2021 Rupert Taylor

Comments

Rupert Taylor (author) from Waterloo, Ontario, Canada on October 12, 2021:

Yes indeed, silly hats

However, I did once wear one (rented) as I was an usher at a friends rather posh wedding.

Miebakagh Fiberesima from Port Harcourt, Rivers State, NIGERIA. on October 12, 2021:

"silly looking hat"? I ginggle. It seems you would not like me dressed in one.

MariaMontgomery from Coastal Alabama, USA on October 12, 2021:

Thanks for a well-written and informative article. We don't think of top hats very often these days, but it was fun looking back on their history. I enjoyed reading it.

Shauna L Bowling from Central Florida on October 12, 2021:

Now I know where the term, "mad as a hatter" comes from. Pretty interesting history of this silly looking hat, Rupert!

Joanne Hayle from Wiltshire, U.K. on October 01, 2021:

Thanks for the information...enjoyed reading this:-)

Miebakagh Fiberesima from Port Harcourt, Rivers State, NIGERIA. on September 29, 2021:

Rupert, the read is a delightful. The hat looks beautiful and comical on the head. The men who wears them seems to be jovial always. Thanks for sharing.