Orientalism in Western Costume

Dolores's interest in fashion history dates from her teenage years when vintage apparel was widely available in thrift stores.

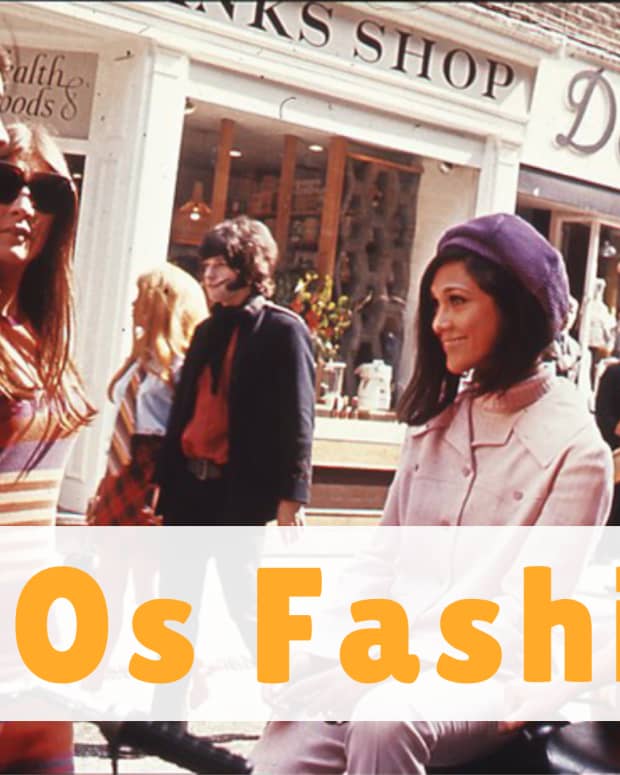

A French ad depicts a kimono clad Euopean woman in a dominant position above kneeling Japanese woman

Downloaded by user Malau on Wikimedia commons' Public Domain

How the West Views the East

Orientalism refers to Asian styles and concepts as interpreted and presented by people of the West. Although trades routes have existed since ancient times, changes in trade, invasions, wars, and the increasing movement of people in the Middle Ages introduced new ideas, designs, fabrics, and elements of Asian costume to Europe. Western viewpoints colored by limited perception offered Asia to Europeans as a fairy-tale-like land of mystery and novelty.

The first known use of the word "Oriental" occurred in the 14th century and referred to any area east or southeast of Europe. While many in the West admired the fabrics and designs of the East, many viewed Asia and the Middle East as unchristian and barbaric and pretended that invasion and colonization was liberation. India fell under British rule in order to empower and enrich the East India Company.

There is a fine line between admiration and cultural appropriation. Appreciation for Asian textiles and the less structured costume of the East contrasts with the use of religious symbols as decoration. Admiration for the softer lines and drapery of feminine garments contrasts with the inappropriately sexualized view of Asian women. Orientalism is as old and complex as human history and has been an influence on how Western people have dressed for a long time.

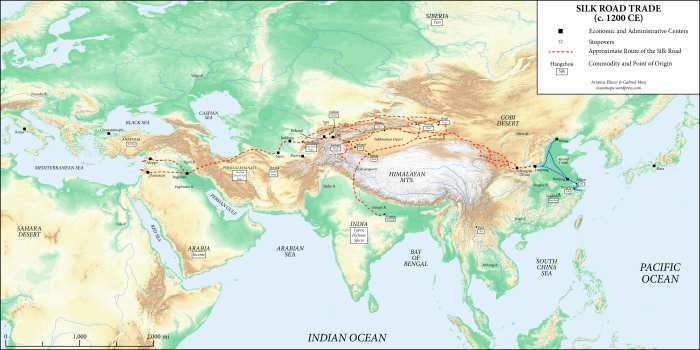

The Silk Road

The Ancient World

The Silk Road, a term coined by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877, refers to trade routes between Persia and China from 500–300 BCE until 1453 CE. Traded items moved from Egypt, through Persia, Turkey, and India to China and included silk, gunpowder, and spices. China kept the production of silk a secret. Byzantine Emperor Justinian (who reigned 527–565 CE) sent spies to China to steal those secrets. The spies returned with the silkworms that gave birth to a Byzantine silk industry that produced luxurious textiles for the elite.

Alexander the Great (527–565 BCE) sometimes adopted the costume of lands that he invaded. Plutarch said that Alexander "first put on the barbaric dress perhaps with the view of making the work of civilizing the Persians easier as nothing gains more upon men than a conformity to their customs." Alexander mixed costumes of various cultures and incorporated foreign customs in his attempt to subjugate the known world.

When the Ottoman Turks invaded Constantinople in 1453, the Byzantine Empire, already weakened by the destruction caused by crusaders, fell. Trade routes to the East were cut off to Europe.

The Crusades

In 1091 Pope Urban sent an army to the Middle East in order to establish Christianity and gain European control over the area. For two hundred years, various crusades sought to bring Christian civilization to "barbaric" Islamic lands. Instead of savages, crusaders found a refined culture of well-dressed people. In Egypt, Fatimid Cairo presented a middle class and a society based on religious tolerance.

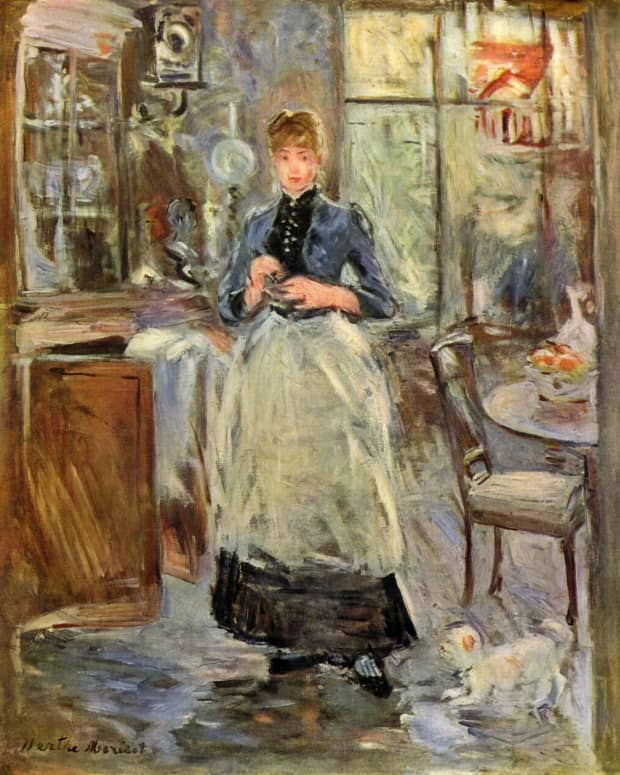

At the time, the people of Europe dressed in fairly plain clothing with few embellishments. Garments were tailored, and the fabric was without any patterns. European clothing was a statement of class, occupation, and function reflecting a static class system.

Middle Eastern costume was less structured than the costume of Europe. Robes and flowing garments featured stripes, embroidery, printed, and checked designs. Beautiful silk robes were given as honors, and upward mobility was reflected in the wearing of more refined clothing. The idea that status could be earned through deeds, or trade rather than birth intrigued many Europeans.

Crusaders brought these new ideas along with textiles home. The novelty and beauty of new types of fabrics fascinated Europeans and impacted the way they dressed as well as how they viewed their static society. Islamic textiles appeared in Christian churches. Women's dresses became longer with flowing trains. Headgear became more ornate. Even monks returned from the Holy Land clad, shockingly, in striped robes.

Middle Ages

The clothing of the Middle Ages was influenced by the perceived ideals of the East. Middle Eastern costume gave rise to the fairy tale quality often associated with that time. The merchant class proclaimed their wealth by wearing fine fabrics with complex patterns, embroidered inscriptions, and metallic threads. Men wore poulaines, pointy-toed shoes whose length indicated status and wealth. Turbans became popular headgear for men.

The Church grew concerned over what they viewed as the decadence of an emerging class that wore their new-found status in luxurious materials. Government officials worried that displays of new wealth upset the old social structure. The hunger for extravagance led to financial concerns as some members of the monied class fell into bankruptcy when they spent all their money on clothing.

Sumptuary laws, established to constrain extravagance, limited the use of luxurious fabric by law. The toe length of poulaines was restricted by class. The height of hennins, tall conical hats worn by women was regulated by class. While a princess could wear her hennin up to a yard in height, members of nobility were restricted to 24" tall headpieces.

Direct Trade With China

While trade routes to the East had been in place since ancient times, the Polo family were the first Christian Central Europeans to have direct contact with the area we know today as China. Nicolo and Matteo Polo traveled to China in 1260. In 1271 they returned to China with Nicolo's son, Marco. Marco Polo traveled extensively throughout China as well as Indochina and Myanmar. Polo presented China as a technologically superior culture. His book The Travels of Marco Polo was one of the most widely read books in Europe. Hungry for novelty and innovation, Europe pursued trade with China, importing spices, technology, dishware, and fabrics. Beguiled by new designs and concepts yet lacking in a real understanding of the distant land, Westerners filled the gaps of ignorance with fantasy.

The East India Company

Until the 18th century, India produced more technologically advanced textiles than Europe. The intense colors produced by mordant dyes created fabrics with brilliant colors that did not fade. Patterns based on nature included stylized florals, animals, birds, and intricate borders. The greatest textile producer in the world, India gave us calico, cotton, Pashmina, and chintz.

Indian words came into common English usage by way of the textile trade, including "pajama," "dungaree," "khaki," and "calico." Their dyes created beautiful, deep colors. Indigo offered an intense blue that Europe was unable to produce with woad. Tumeric produced yellows, and alizarin produced bright red.

Read More From Bellatory

In the 1500s, Portugal had a monopoly on Indian textiles, introducing calico to Europe. By 1630, the Dutch earned 65–160% profit from their Indian textile trade.

In the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, England sent ships to the Indian port of Surat. A merchants group called the East India Company established factories in 1615, then expanded creating English communities and trade operations in Calcutta, Mumbai, and Madras. Commercial expansion, fueled by the might makes right mentality, led to war and plunder. The East India Company created its own army and levied taxes on the inhabitants of the region. Formerly wealthy Indian states ravaged by war fell into poverty. A famine in 1769–70 decimated the population.

An uprising in 1857 led to the abolition of the East India Company. The British government stepped in and created the British Raj and making Queen Victoria the Empress of India. British occupation of India led to the subjugation of the Indian people who remained under British rule until 1947.

"A Lady From Hindoostan" circa 1809

From the French magazine Beau Monde Source: Downloaded by user FAE on wikimedia commons; PD

Japan

From 1639 until the mid 19th century, Japan remained isolated from the West. In order to establish an Eastern Pacific safe harbor and supply station, Commander Matthew Perry of the U.S. sailed four ships into Tokyo Bay. Reluctant Japanese authorities capitulated to the threat of force. Eventually, trade pacts were established.

A popular surge of Japanese style soon followed with a Japanese influence on art and design. Crashing waves, chrysanthemums, woodblock prints, and fish patterns soon appeared in Western textiles. Though elements of kimono style had appeared in the past, new less-structured garments similar to kimonos showed up in Victorian tea gowns.

French designers like Charles Frederick Worth incorporated loose sleeves and the crossed bodice of kimonos into his evening dress designs.

In the 1870s, Japan's silk production methods proved superior to that of other countries leading to Japan cornering the silk market in Europe and the United States of America.

In the early 1900s, Madeline Violet designed kimono style garments using minimal cutting. Elizabeth Hawes created Japanese inspired clothing in the 1930s using modern kimono fabric.

1872 Painting Blue Kimono by William Kay Blacklock

Downloaded by user Amanda 44 on wikimedia commons. Pd

The Great Exhibitions

The Victorian era introduced a number of huge exhibitions that featured foreign cultures. Exhibitions in Europe and the U.S. offered a supposed glimpse into the lives of colonial subjects. Often depicted a backward and referred to as "savages," people were displayed in human zoos. Mock villages were set up to show how "exotic" people lived. Sometimes people were displayed in actual zoos, in cages alongside animals.

The depiction of the supposed inferior people of colonized areas of the world encouraged visitors to appreciate the civilizing influence of the colonists.

At the same time, Westerners loved the textiles and designs of Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Artists and designers of the Aesthetic Movement, a group that stood against modern production methods and the loss of craftsmanship, looked to the East (as well as medieval Europe) for inspiration. An appreciation of less structured, more draped garments led to a style highlighted by beauty and comfort.

Liberty's of London

In the late 1800s, a craze for all things Asian inspired Farmer and Rogers Oriental Warehouse, a store that offered Kashmir shawls, fabrics, and Oriental goods. Arthur Lasenby Liberty managed the Oriental Warehouse until he opened his own store Liberty's of London, which became an iconic shopping destination.

Liberty's offered Middle Eastern and Asian goods in the Basement Eastern Bazaar. The shop sold imported silks, naturally dyed fabrics, hand-painted fabrics, tea gowns, and kimonos. Liberty's produced fabrics designed in collaboration with Pre Raphaelite artists like Dante Gabriel Rosetti, and William Morris. The Pre Raphaelite Movement designers favored the Dress Reform Movement, a concept that rejected stiff tailoring and the wearing of corsets in favor of more gracefully draped garments with an Asian influence.

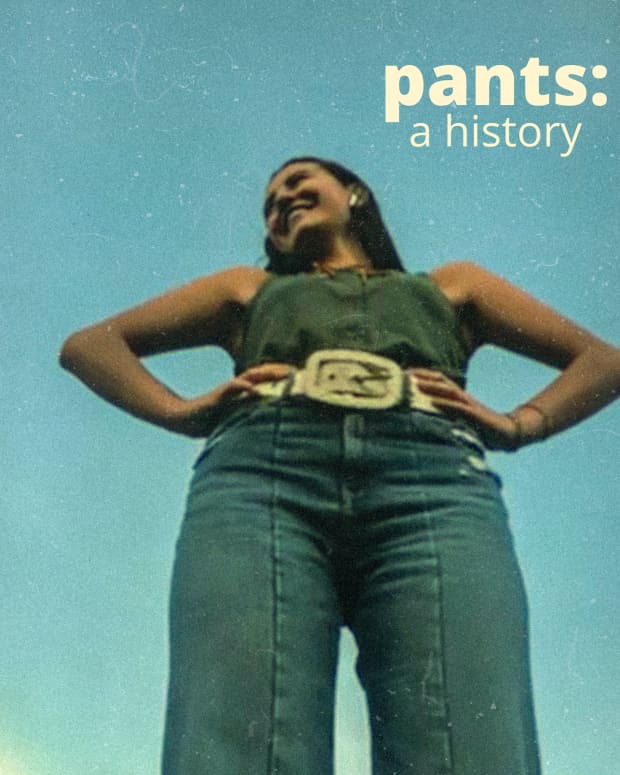

Dress reformers of the late 1800s introduced Turkish trousers worn with a knee-length dress as a more practical way for women to dress. The concept fell flat and did not return until the 20th century.

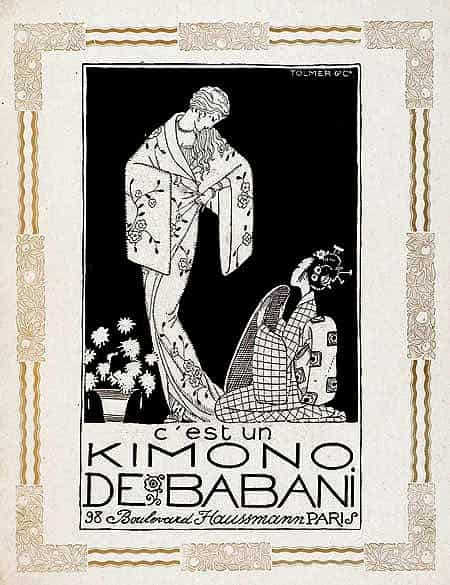

Poster for 1914's Scheherezade; costumes designed by Leon Bakst

Downloaded by user Seraphim System on wikimedia commons' Public Domain

Paul Poirot's design based on harem costume at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Downloaded by user Pharog on wikimedia commons; PD

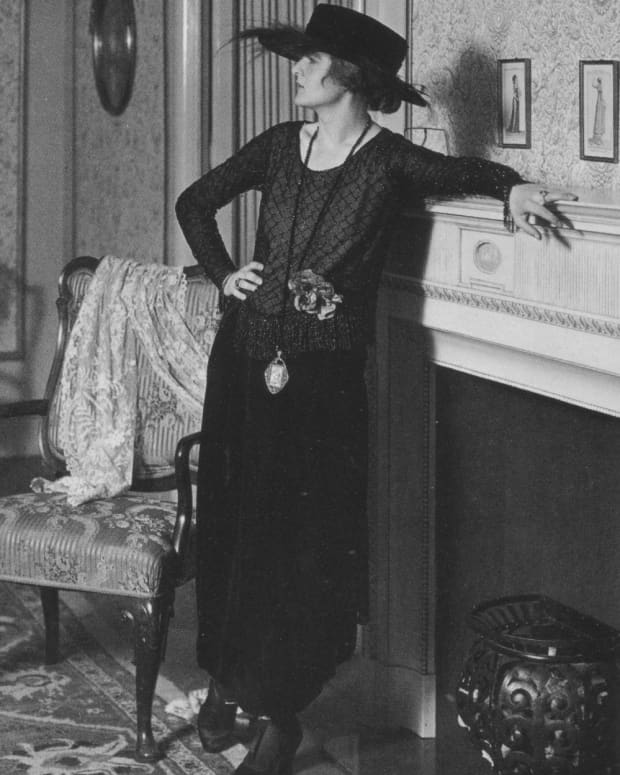

Orientalism in the 20th Century

Western interest in Eastern clothing and textiles continued into the 20th century. Fashion designers like Paul Poiret and Mariano Fortuny created exotic styles based on Middle Eastern and Asian motifs.

Paul Poiret, inspired by Leon Bakst's costumes for the Russian Ballet, designed garments that featured tunics worn with harem pants which were full in the leg and gathered at the ankle. Turbans became popular headgear. Mariano Fortuny used Japanese and southeast Asian hand block printing methods on his fabrics. He designed garments influenced by Moroccan djellaba, Arabic abaya, kimonos, Coptic tunics, and Indian saris.

When Howard Carter opened the Tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun (King Tut) in Egypt in 1922, a craze for ancient Egyptian influenced fashion soon followed. Sheath dresses featured beaded necklines that recalled an ancient Egyptian broad collar. Pleated skirts echoed the ancient Egyptian style. And jewelry designs based on the beautiful jewels found in the tomb became popular.

Early 20th-century pulp magazines, stage shows, and films portrayed women of North Africa, the Middle East, and China as hypersexualized femme fetales. Up into mid-century, movies featured Chinese and Japanese women as either meek and subservient or as a scheming dragon lady, an exotic predatory female. The 1960 film, The World of Suzy Wong used a respectable garment called a cheongsam to glamorize a prostitute in the film.

During World War II, the West turned away from Japanese influences. Fabric and material restriction led to simple, tailored women's clothing for some years during and right after the war.

In 1948, Christian Dior created models he christened Chino, Shanghai, and later designed Hong Kong, and Chinoseries.

The hippie movement of the 1960s brought a new interest in the East. People of this new Bohemian counter culture rejected the stiff tailoring that was a hallmark of mid-century style. A new interest in Eastern design, music, religion, and philosophy created a whole new fashion. Of course, for the most part, real interest was shallow and more about how things looked.

Middle Eastern kaftans became popular garments for their comfort and exotic appeal. Paisley prints based on an old Indian design motif became an iconic feature of hippie trends.

The Nehru jacket briefly offered an alternative to classic Western suit jackets. A high round collar appeared above a front button closure on a long jacket similar to a jacket worn by Independent India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Long beads similar to Indian meditation beads were often paired with the jacket.

In 1978, Edward Said published Orientalism in which he portrayed the West's off and on obsessions with all things Eastern as a paternalistic, imperialistic view of all non-Western people and their cultures. Said encouraged readers to attempt to understand traditional Western perceptions in a new light.

Late 20th Century–Today

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st, haute couture designers found inspiration in Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Coco Chanel, Yves St. Laurent, Jean Paul Gaultier, Alexander McQueen, and Vivienne Westwood all created garments based on non-Western culture.

John Galliano produced "A Voyage on the Disorient Express" for the House of Dior in the fall/winter of 1998–99. The title of the show appears to poke fun at either the Chinese influence or his own take on the culture. His 2003 designs included motifs inspired by Chinese opera. In 2007, Dior's collection included a dress with a version of Katshushika Holusai's famous Great Wave off the Coast of Kanagawa hand-painted on the skirt.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art's show China Through the Looking Glass in 2015 recalled Alice's famous journey through a fantastic and nonsensical world. The show's concept was to depict the power of textile and costume, how costume informs our view of other cultures in both positive and negative ways. The work of Chinese artists and designers was included in the show.

Amanda Holpuch in the Guardian said that China Through the Looking Glass was, as is Orientalism in general, not so much about China as about our "collective fantasy about China."

In the book Orientalism Visions of the East in Western Dress, Harold Koda and Richard Morton state that the "inscrutability attributed to the East is, in fact, the West's failure achieve full comprehension."

From the Metropolitan Museum of Art's "China Through the Looking Glass" 2015

Downloaded by user Getareu8

Sources

Fashion and Orientalism - Dress, Textiles, and Culture from the 17th Century to the 21st Century by Adam Geczy; A & CBlack; NY; 2013

Orientalism - Visions of the East in Western Dress by Richard Martin and Harold Koda, Metropolitan Museum of Art; NY; 1994

Our Oriental Heritage by Will Durant; Simon and Schuster; NY; 1954

MET's China Through the Looking Glass Presents a Fantasy of the Far East by Amanda Holpuch; The Guardian; May 4, 2015

John Galliano on Why He Loves Chinese Motifs by Mark Guiducci; Vogue; April 21, 2015

© 2018 Dolores Monet