Women's Clothing in the Historic American West

Dolores's interest in fashion history dates from her teenage years when vintage apparel was widely available in thrift stores.

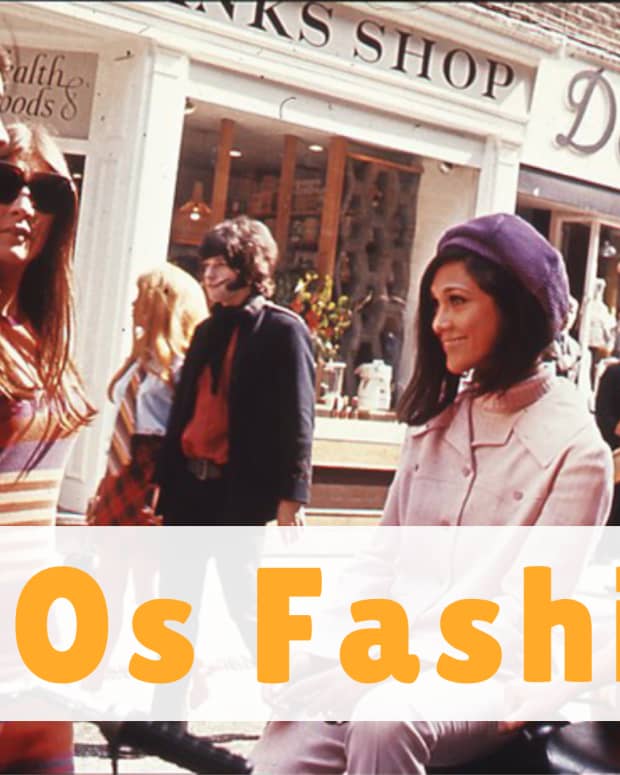

Historical Dress of the American West

The clothing of women in the historic American West encompasses a wide variety of styles, construction, and materials, depending on climate, ethnic tradition, socioeconomic status, and availability of materials.

The type of garments women wore also depended on occasion. Everyday clothing needed to be simple for ease of movement while working, as well as tough and durable. Most women in the Old West (as well as everywhere else) owned far fewer garments than modern women. Clothing was handmade, and resources were limited. Special occasions called for garments made of finer materials, more complicated construction, and embellishments.

The type of clothing women wore also varied due to climate, from the harsh winds of the prairie to the cold winters of the Rocky Mountains, from the wide daily temperature fluctuations of desert regions to the moist Pacific Northwest.

There was no single Western style in the vast area that stretched from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean and from Canada to Mexico. Between 1830–1900, the American West was home to a wide diversity of indigenous nations and tribes, Spanish speaking people of the Southwest, Chinese and European immigrants, African Americans, and white Americans from the East. As people adapted to changing circumstances and resources, clothing changed with white women wearing fringed buckskin and indigenous women wearing Victorian garments.

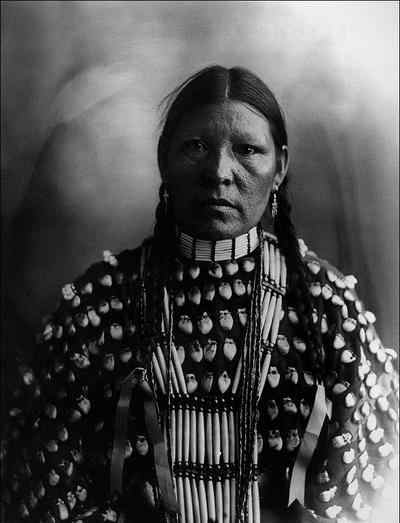

Freckle Face, an Arapaho woman in a shirt decorated with elk teeth, wearing hairpipe jewelry.

wikimedia commons, public domain

Indigenous Peoples of the Americas

Clothing of Indigenous American women depended on locale, resources, tribal affiliation, occasion, and status. While daily wear was usually simple, women wore fancier clothing for special occasions that featured more complicated work, as well as decorative elements like fringe, animal teeth, porcupine quillwork, silver, turquoise, abalone, and beads made of shell and bone (later glass and ceramic).

Women of the Great Plains

Indigenous American women of the Great Plains used the hides of antelope, deer, and elk to make soft dresses, tunics, and leggings.

Sioux Women

Sioux women typically wore a knee-length dress or tunic, in a loose T-shirt style, with variations depending on tribe, marital status, socioeconomic status, and occasion. A woman married to a highly-skilled hunter would incorporate more elk teeth than the wife of a less successful hunter. Bones could also be made to look like elk teeth.

Lakota Women

Dresses with heavily beaded yokes were worn by Lakota women for special occasions. Blue, symbolizing water, was the most popular color between 1850 - 1870.

Cheyenne, Osage, Chippewa, and Pawnee Women

Women wore a two-piece outfit consisting of a skirt and cape. Chippewa women incorporated floral designs into their garments while Lakota women used geometric shapes in their designs.

Other Great Plains Dress

Moccasins varied depending on tribe and climate. In winter, moccasins were lined with fur for warmth. They could be elaborately embellished for special occasions. Buffalo robes were worn for the cold winter prairie.

Trade cloth became an essential element in the late 1800s. When the bison were exterminated by white hunters and game became scarce, women used milled fabric brought from the East to create traditional-style garments or garments influenced by Victorian styles.

Hair usually hung in two braids, which could be decorated with leather strips, bones, shells, or other natural objects.

Ornate jewelry was made of trade goods like shells. Hairpipe, tubular beads made of shell or bird bones, were used to make chokers, necklaces, earrings, and decorations for hair. Quillwork was a popular element used for bracelets, earrings, and hair clips.

Read More From Bellatory

Women of the Southwest

Indigenous American women of the Southwest used deerskin, sheepskin, wool, and cotton for clothing construction. Upright looms, used since at least 1200 CE, were used to make fabric of wool or cotton, which was grown in some areas cultivated from a wild form of cotton.

European Influence on Clothing

In the 16th century, Spanish invaders brought the Churra sheep to the New World. The hardy breed was well-suited for the harsh environment and soon became popular with Southwestern tribes for food and weaving. Early woven goods were produced in neutral colors with the occasional use of indigo (acquired by trade). Later, bright colors were incorporated by a raveling technique where other fabrics were taken apart and the wool thread reused for unique designs.

In the mid-1800s, the American government decimated the South West tribes, as well as flocks of what had become known as Navajo churro. Women turned to mill produced fabrics to create traditional-style garments like mantas and conchos (a stamped or inlaid silver ornament), as well as European inspired styles like three- or four-tiered skirts.

Navajo and Hopi Women

Navajo and Hopi women wore their hair in a chongo, hair tied in a twist at the back of the head. Unmarried women wore their hair in squash blossom whorls, elaborate hairdos featuring a whorl of hair on each side of the head.

Women wore moccasins, often colored white with kaolin white clay. The clay was also used to create white buckskin dresses.

Pre-Spanish jewelry consisted of pendants made of shells, coral, and beads. In the 1800s, silver became the new traditional jewelry for necklaces, earrings, bracelets, rings, and other decorations on conchos. Turquoise had long been worn in jewelry and associated with the sky, strength, and good fortune.

Women of the Pacific Northwest

Rich natural resources of the Pacific Northwest encouraged an Indigenous American population denser than other areas. Tlinget and Suquamish women made fabric out of red cedar bark while the Pomo used redwood bark. Tree bark was dried and shredded to weave shirts and aprons.

Inland tribes relied on deer for buckskin dresses and leggings that were trimmed with fringe on the bottom of the skirts and the ends of the sleeves. Animal teeth, claws, bones, and walrus tusk ivory were used to make jewelry including bracelets and necklaces. Women of high status wore pendants made of abalone shells.

Inland women wove basketry hats featuring geometric designs.

Clothing of the Elite Immigrants

The West offered more opportunities to women than their eastern counterparts. Spanish speaking women of the Southwest retained control of marital property after the death of their husbands. They also owned half of the property in marriage, unlike women in the East. Female owned ranches provided some women with great wealth.

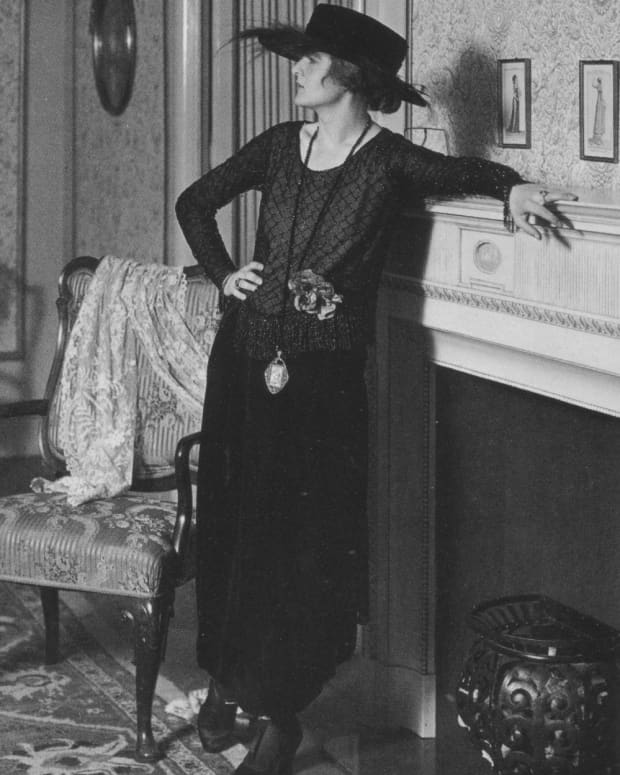

Clothing followed the Victorian fashion of the day. Wealthy women hired seamstresses to create their garments. Low cut necklines and short sleeves were worn for evening and formal occasions. High necklines and long sleeves were worn during the day. Fabrics included silk, linen, brocades, and velvet.

- The 1830s: Fashions of the 1830s featured full, puffy sleeves with the puffs worn low on the arm with long sleeves, higher on the arm for evening dresses with shorter sleeves. Skirts were dome-shaped and pleated. Capelets or trippets draped over the shoulders like a mini shawl. Hair was parted in the center, pulled into a bun at the back of the head, or coiled into braids for a top knot. Curls hung at the side of the head.

- The 1840s: In the 1840s, full dome-shaped skirts with wide flounces were worn over layers of petticoats. Sleeves were worn tight at the top of the arm but flared out below the elbow. Hair was worn in a bun at the back of the head, or in a braided top knot with side curls framing the face. Hair could be pulled back smoothly or looped at the side of the head in a style that resembles a bob.

- The 1850s: In the 1850s, wide domed shaped skirts worn over layers of crinoline were the rage. Tiers and flounces decorated skirts—lace, ruching, and ribbons decorated dresses made of silk or other fine fabrics. Hairstyles featured a center part with side curls and a bun worn at the back.

- The 1860s: By the 1860s, fullness appeared at the back of the skirt, which was flatter in front than in the 1850s. Tight bodices featured a low shoulder line and wide, flared sleeves with lace collar and cuffs.

- The 1870s: In the 1870s, skirts were layered and trimmed in ruffles and flounces with bustles accenting the rear of the skirt. Tight bodices fell to the hips with either tight or slight bell-shaped sleeves. Hair pulled toward the back with curls cascading down the back of the head.

- The 1880s: In the1880s, skirts were narrow with lots of ruffles and trim. Mid-decade, skirts widened, and the bustle reappeared. Later, an overskirt draped horizontally or diagonally in the front. Bodices were shorter with pointed Vs at the bottom and high collars with white ruffles.

Before the advent of the railroad, even the wealthy were constrained by the vast distances of the American West. Influential fashion magazines like Godey's Lady's Book, as well as fabrics, took months to reach women in the West, so new clothing styles appeared much later than in the East.

The Transcontinental Railroad (1869) improved travel, communication, and the availability of information, fabrics, and decorative elements. This helped the Western elite become more up to date.

Elizabeth McCourt Tabor (1854–1935) was one of the best dressed women in the West. Her life was a rags to riches to rags story.

Downloaded by Gabonobo on wikimedia commons

The Chrisman sisters pose in front of a sod house.

Photo by Solomon D. Butcher; wikimedia commons; public domain

Clothing of the Pioneers

Most women of the time owned few garments, one or two day-dresses and an outfit for special occasions. Everyday garments were simple while Sunday dress, made of finer materials, featured more tailoring, detail, and embellishments. Hemlines for day wear usually fell shorter than those of women in the East.

Pioneer women worked hard. Women needed tough, durable clothing. Fabrics included:

- Linsey-woolsey: Linsey-woolsey was a warm, durable, and inexpensive fabric. It was made with a linen warp and wool weft. Later, cotton replaced linen.

- Osnaburg: Osnaburg was a cheap, loosely woven fabric made of flax and later cotton.

- Homespun: Homespun fabric was spun and woven at home. The look and texture depended on the skill of the weaver.

- Buckskin: Buckskin was made of softened deer hide. It protected the body from the wind and was tough and durable.

- Jean: Jean was a cotton fabric that was similar to denim but more lightweight.

- Muslin: Muslin was a cotton fabric used for undergarments and as a lining material.

- Linen: Linen was made of flax, an early crop often grown by pioneers. Though making linen was labor-intensive, the only cost was for the seeds.

- Calico: Calico was cotton printed with three or four colors, usually dark florals as dark colors hide stains.

Women wore Mother Hubbard dresses, which were loose-yoke topped, waistless garments with high necks and long sleeves. Aprons created a waistline. Aprons were an essential part of a woman's wardrobe as they protected dresses, skirts, and bodices from soil or stains.

Women who lived in town who were teachers or middle-class, dressed in a more stylish manner than women who worked on ranches and farms.

Most women made their own clothes during the winter. Fabric remnants or pieces of worn-out garments were used to make aprons, bonnets, collars, cuffs, curtains, and clothing for children.

Bonnets were also made of scrap cloth with stiffening in the lining. An extended brim in front and an apron that hung down the back of the neck protected the skin from the sun and blowing dirt, as well as shaded the eyes. Bonnets sported decorative ruffles, piping, braiding, or ribbons. Special occasion bonnets matched Sunday dress.

Pioneers brought shoes and boots with them on the wagon train. Women also made moccasins from buckskin.

By 1895 mail order catalogs like Sears and Montgomery Ward offered corsets, hats, skirts, blouses (called waists), gloves, shoes, and other ready made garments, accessories, and notions.

Undergarments

Pioneer women strove to maintain their dignity in the face of harsh circumstances. They adhered to European traditional dress by wearing corsets, especially when visiting, and for going to town or church. There are photographs of women traveling with wagon trains who are obviously corseted.

Wearing a corset was not a choice in those days; it was just done. Whether they wore corsets under loose dresses while working is anyone's guess. Undergarments were rarely mentioned in diaries, hence the old term for underwear, "unmentionables." The term "loose woman" means a woman without a corset.

A chemise was a loose, linen or muslin shift worn under the corset. This short-sleeved, knee or calf-length garment protected dresses from perspiration. The wide neckline featured a drawstring. A chemise could be worn for sleep instead of a nightgown.

Drawers were optional but often worn in colder months for added warmth.

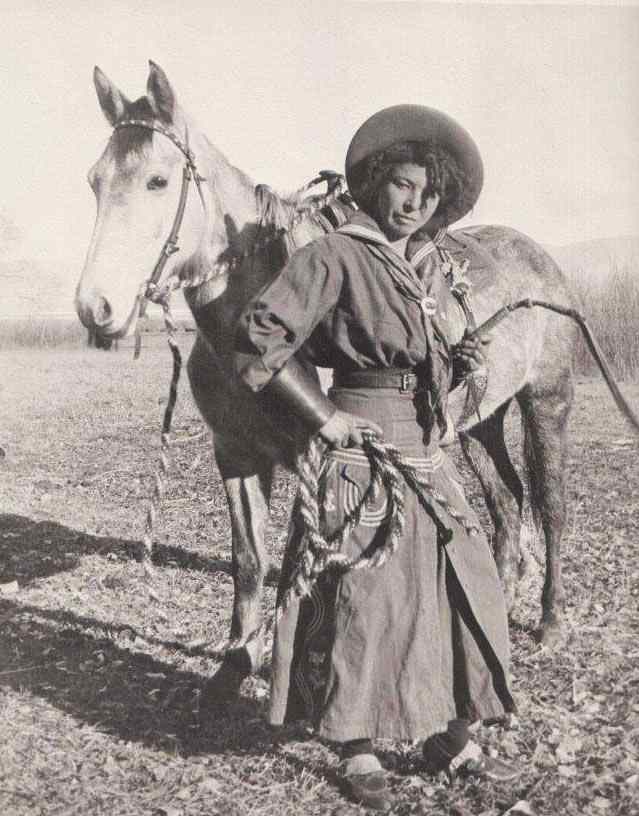

If you look closely you'll see that the horse is wearing a sidesaddle.

DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University; wikimedia commons; public domain

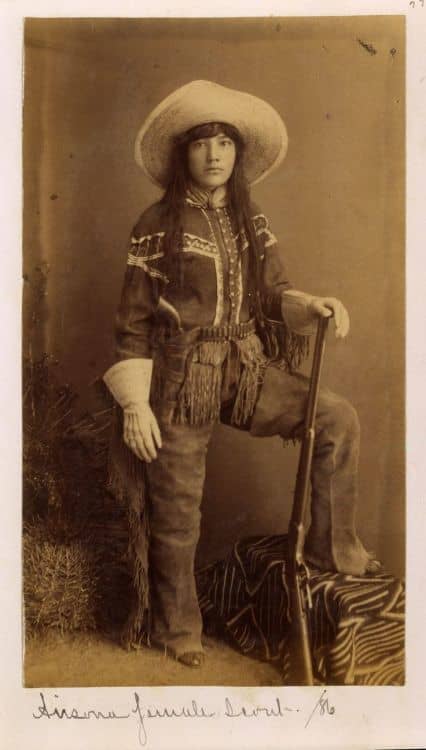

Cowgirls and Characters

It seems crazy to think that women rode sidesaddle with both legs hanging over the same side of a horse. Few women rode astride until the early 1900s. Of course there were outliers like Calamity Jane who often posed for photographs dressed like a man. Stagecoach Mary Fields (the first African American woman to work as a contractor for the U.S. Postal Service driving a stagecoach) wore pants. The Spanish speaking woman from Texas at the top of the article is wearing pants. But, for the most part, women wore long dresses.

If you look closely at the photograph above, you can see the pommel of the saddle is off to the side—a feature unique to a sidesaddle.

"My sister, Mattie, just older than me, could ride, rope, and shoot as good as anybody I ever saw. I've seen her on some pretty mean horses, riding her side-saddle but she sure could handle them." — Mrs. Mary Leakey Miles from Folkstuff and Folkways, U. S. Library of Congress

In the early 1900s, women began to wear divided skirts in order to ride astride, a practice once seen as vulgar and inappropriate. Short, calf-length skirts were worn by performers, entertainers, and sharpshooters like Annie Oakley.

For Further Reading

How the West Was Worn: Bustles and Buckskins in the Wild Frontier by Chris Enss

Calico Dresses and Buffalo Robes American West Fashions From the 1840s–1890s by Katherine Kruhn

Native American Clothing: An Illustrated History by Theodore Brasser

African American Women of the Old West by Tricia Martineau

Black Women of the Old West by Loren Katz

Testimonos: Early California Through the Eyes of Women by Rose Marie Beebe

Dress of the Oregon Trail Emigrants 1843–1855 Iowa State University

© 2020 Dolores Monet

Comments

Dolores Monet (author) from East Coast, United States on February 24, 2020:

Hi Genna - some garments were spot cleaned with home made cleaning fluids with ingredients like turpentine, honey, gin, and French clay. Cottons (like calico and muslin), jean, and linen was cleaned in a large tub with lye soap and hot water.

A "dolly" was a large stick with what looked like a small stool at the bottom used to agitate clothing in hot water. Many garments were soaked overnight. Boiled water was mixed with soap and allowed to cool before soaking clothes.

For certain stains onion or lemon juice came in handy. Borax was introduced in the late 1800s and kept fabric from fading. Vinegar was used as a cleaning agent and prevented the fading of pinks and greens.

Washed garments were dried on a line, spread on bushes or on the ground to dry in the sun. The clothes were starched with home made starch (easy to do, I've done it myself) then ironed. A heavy iron was heated on the stove before being used to press clothing.

Genna East from Massachusetts, USA on February 23, 2020:

What an interesting and entertaining article. Whether deerskin, wool, silk, linen, etc., I've often wondered how women kept their garments clean. Thank you for this delightful read.