Slaves to Fashion: A Brief History and Analysis of Women's Fashion in America

I'm an aspiring costume designer with a passion for creative writing, history, and feminism.

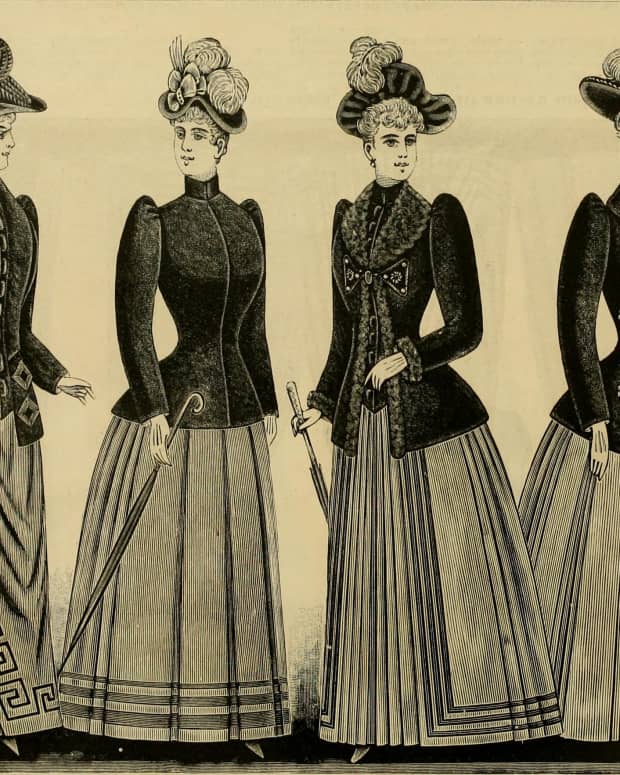

American Fashion, 1780s. L. Suit in French style; LC. Gown in French style; RC. and R. suit and gown

American Women's Fashion History

Clothes make the man, as the old adage goes. A well-tailored suit tells a very different story than torn jeans and a sweatshirt, but both stories are vital when trying to understand the evolution of fashion and the impact it has made. Regardless of whether or not we like it, fashion has played an intrinsic role in shaping society. It is a way to understand the world and those who came before us.

For instance, different fashion trends are a marker of status as well as a window into attitudes toward gender roles, sexuality, and body image. Clothes may make the man, but they make the woman as well. In fact, clothes often molded her and constricted her into a form that she may not have wanted for herself. Clothes have empowered her and encouraged her to achieve her own sense of autonomy. They have objectified her and reduced her into nothing more than a trinket at which men can stare. They have given her power and a taste of what she is capable of doing.

Colonial Women's Fashion: Family & Practicality

When discussing the impact of anything on a nation’s history, the most logical place to start is at the beginning. There are, of course, centuries prior to European colonization in which Native American tribes developed methods and modes for dressing themselves that are varied and intriguing on their own, but they have little to do with the modern modes of fashion as we know them today. The focus will instead turn toward fashion modes of European settlers – specifically those that hailed from England – for whom the New World held promises of freedom from religious persecution and a bright future potentially full of riches, though despite the prospect of a shining new future, colonists carried over a few societal norms from their home that remained firmly in place in their new settlements. Gender relations, for instance, reflected that of the roles established in the motherland: New England women were expected to maintain order in the household by caring for children and acting as a moral compass by which to follow, preparing meals as well as performing other household chores. Despite her numerous responsibilities and power in the home, a woman was always expected to be subordinate and obedient to her husband. Families were ideally little commonwealths with the father taking the role of a monarch while the rest of his family acted as his subjects -- the general belief here being that a successfully run home would facilitate a successful society.

New Englanders had an understanding that men and women’s characters were defined by a specific set of distinct yet complementary traits. Women were overly sexual, disorderly, and prone to hysteria and the lures of evil, but their positive traits included cheerfulness, tenderness, and a capacity to be sympathetic and passionate. Since it was a woman’s task to keep her family thriving in this unexplored wilderness, such virtues were nothing more than expectation rather than reality. Their clothing, like their societal ideals, reflected a simplified version of what was fashionable in England at the time. Their clothing was designed for practicality in a harsh new wilderness rather than style. Fabric was hand woven to ensure durability and most early New Englanders only owned a few garments for their entire lifetimes, only saving their best for special occasions and church services. They were no strangers to an array of colors despite what the general stereotypical image of a New England pilgrim may lead one to believe. On the contrary, the stereotypical, somber appearance of colonists did not appear until the colonies were beginning to thrive. In a prosperous and environment, people were now able to turn their attention to such frivolities as fashion to display their wealth and comfort. As a response to such brazen and apparently immoral displays of refinery, Puritans attempted to enforce laws that brought simplicity to an extreme by eliminating any sort of decorative feature, leading to a distinctive style to call their own.

Hoop petticoat or pannier, English, 1750-80. Plain-woven linen and cane. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2007.211.198.

Women's Fashion Trends and Styles in the 18th & 19th Centuries

Despite the Puritans’ best efforts, fashion continued to play a large role in most colonials' lives the more the colonies grew and prospered. While women wore hoods and mantles to maintain their modesty when in public, such garments were made of fine fabrics that not only acted as a testament to their piety, but to their status. The most notable garment to come out of the century was the hoop skirt, which would become a staple of women’s fashion for years. Originally, the hoop skirt protruded out from the sides but gradually became rounder and more bell-shaped, though no matter how large or oddly shaped the garment may have been, it always gave women a grossly unnatural figure that they were expected to obtain. Adding to the extravagant and outlandish silhouettes were ladies’ hairstyles. Initially, hairstyles stayed simple and women typically adorned their heads with a frilled lawn cap, but by the end of the century, their dainty coiffures gave way to wigs worn exclusively for evening affairs. These elaborate wigs required women to often sleep while sitting up the night before an event to prevent the wig from losing its magnificence. The sheer notion that a woman had to attempt to sleep in an uncomfortable position with an undoubtedly cumbersome wig sitting atop her head illustrates the great lengths to which people have gone through for the sake of fashion and beauty. However, that focus on status and elegance began to fade with the Revolution. Suddenly a dependency on European trends did not seem patriotic in the least. Women began weaving their own cloth and wore homespun clothes in public, an act that would have been an immediate marker of low status in the past that was now considered a symbol of pride and dedication to the nation.

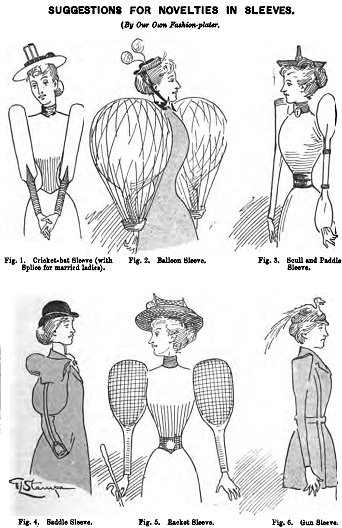

Cartoon mocking sleeve designs suggesting that new styles could be modeled on cricket bats, hot air balloons, or tennis rackets.

Wikipedia

The Evolution of Women's Fashion in the 19th Century

The nineteenth century brought in a new phase of American life that stressed religious freedom, an elimination of class distinction and a rejection of old ideas in many respects. Women were still bound in corsets, but they were less constricting and they abandoned their heels in favor of “Roman sandals,” which were nothing more than slippers tied at the ankle with ribbons. The spencer, or a small jacket with long, tight sleeves typically made of dark velvet, made its appearance during this era, as well. In 1819, women’s empire-waist skirts morphed into large, bell shapes that were often adorned with rows of trimming. Stuffed and wired sleeves humorously referred to as the “leg o’ mutton sleeve” offered an illusion of broader shoulders and copious amounts of ornamentation were back in vogue.

In the nineteenth century, a woman's role as the pure and pious leader of her family was especially heightened, and the most conspicuous way a woman could prove her piety was through the way she dressed, but her style also had to reflect her status and level of wealth. Hoop skirts were still wildly popular, for instance, because they enabled women to parade around in as much expensive fabric as possible. They had to be careful, then, as they constantly had to teeter along a fine line between excellent self-presentation and the risk of being labeled as a slave to fashion. Though since the practice of tight-lacing corsets (which was still rampantly popular in the South) reinforced a woman’s sense of dependency, as she could hardly dress or undress herself without assistance, it is difficult to argue that women were anything but slaves to their clothes.

Skirts flared out and bustles disappeared and reappeared throughout the century, leading to a slew of unique and peculiar silhouettes. Overall, fashion of the nineteenth century was meant to reflect modesty while still maintaining a sense of style, a goal that became especially difficult for women who decided to bid goodbye to their New England homes and make the trek out West. The move Westward was accompanied by a desperate struggle to maintain a higher status and keep within traditional roles. Simply put, most women did not want to be subjected to the difficult tasks that awaited them on the trail. They refused to wear trousers for fear of being labeled too masculine or out of fear of losing their civility. Remaining in their petticoats for as long as possible became a way for these women to signal they were prepared to return to their feminine sphere once their journey was over.

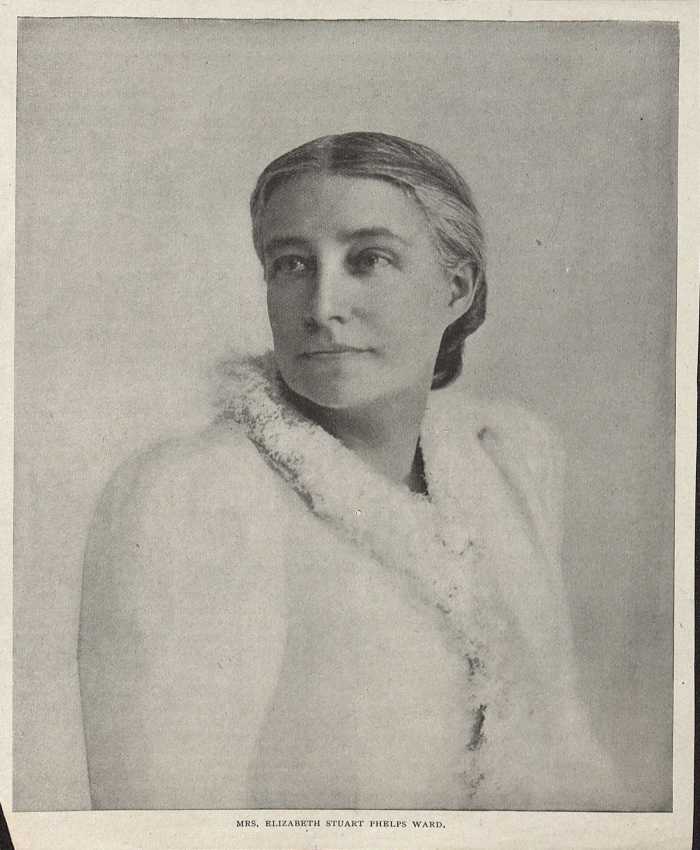

Women who stayed home, however, began to realize the extent to which their fashion objectified them and put them at risk. The anti-slavery movement inspired women such as Elizabeth Phelps to press for dress reform. Women such as Phelps demanded liberation from the limitations thrust upon them by society and fashion, urging women to throw off their shackles just as the slaves had theirs.

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps Ward. (MSS 6997-e. Clifton Waller Barrett Library of American Literature. Image by Petrina Jackson)

The Bloomer Outfit

Dress reformers began openly condemning fashion for the health and moral dangers it posed to women. They pressed for reform for healthy and comfortable clothing, which brought about the bloomer outfit. Such an outfit of course was met with much anxiety since people feared it would destroy society’s morals. Though regardless of the fear it may have sparked, the bloomer outfit served as a preview of what was to come in the following years, particularly regarding the way women viewed themselves and their place.

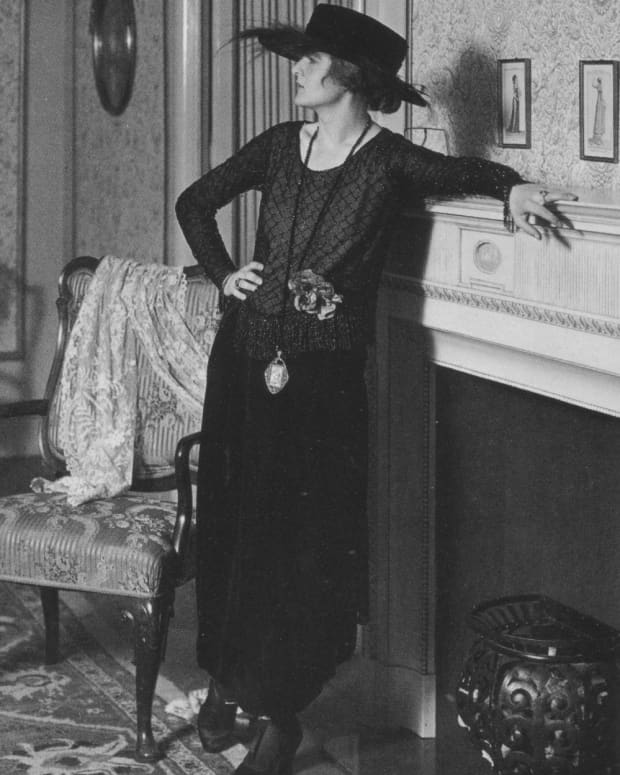

20th Century Fashion: A New Woman

At the turn of the century, America was experiencing rapid urbanization and industrialization. To look at the country as a whole unit at this time, one would see waves of immigrants arriving and countless city dwellers being forced to clump together into crowded slums infamous for high rates of disease and infant mortality. Massive migrations to cities meant that women lost established support systems, resulting in alienation for some and liberation for others. In an environment where young women were isolated from their families and very much left to fend for themselves, women needed to adapt. Thus the New Woman emerged: independent, active, mobile, and self-confident, nothing could stop her and her fashion had to emulate that.

Women’s fashion was altogether more daring and wealthier women were expected to change their clothes three or four times a day. By the beginning of the decade, the perfectly coiffured and slender “Gibson Girl” style that had previously dominated women’s fashion was slowly fading, as women were growing increasingly unwilling to submit themselves to the tortures of the corset, which at the time were made of heavyweight cotton, twill, and reinforced with steel or whalebone to contour the body into an “S” shape, effectively accentuating the bust. Finding her fashion choices limited, a woman by the name of Mary Phelps Jacob created a prototype for the brassiere in 1913, which soon rose in popularity amongst other women looking to become this new, active woman. Ironically, a popular garment that also gained popularity was a tight fitting skirt that greatly limited the wearer’s stride known as a “hobble skirt.” They were popular among urban women until public dancing became the rage for the population in 1915. Sports attire became popular since it flattered women’s bodies while allowing them to move freely. An emphasis was certainly placed on this new, mobile woman, though she was still expected to maintain some air of femininity.

People who were able to flaunt their wealth did so through extravagant and costly accessories that were necessary for anyone who viewed herself as fashionable. Hats, usually adorned with a large variety of ornamentation, were a staple for every woman regardless of economic status. The spread of automobile travel furthered the change in fashion since there was now a need for women to easily enter, sit in and exit vehicles. This led to entirely new outfits comprising of gloves, caps, and goggles for both women and men.

Read More From Bellatory

The elegance and need to flaunt one’s status and wealth was short lived once the First World War began in 1914. In a way, the war helped to accelerate the ideal image of the New Woman as well as the changes women were trying to make in society, as a number of women had to take up men’s responsibilities in the workforce. As a result, working women needed practical clothing. Style was simplified while skirts were shortened, resulting in a tailored suit that became essential for women at the time.

Women's Fashion Trends in the 1920s

Although women lost their jobs when men returned from war, nothing could stop them from careening into the public sphere now that they had a taste of life outside their homes. Jazz bombarded the public’s ears and the Charleston invaded every dance hall. The 1920s was a zooming decade filled with fast cars, flowing bootlegged booze, and an entire generation of women that refused to return home. Regardless of women’s wishes to continue working, a new sort of feminism that supported old, patriarchal expectations of a woman’s place emerged that supported an image of a woman who was well-dressed, openly liked men, avoided women in groups, and instinctively knew that “a full life calls for marriage and children as well as a career.”

The youth of the 1920s were more educated than their mothers and enjoyed a freer life filled with romance and sex, and to separate themselves from their mothers, young women needed a new style to call their own. Sexually free young women who would come to be known as flappers acted as both competition and companions to men and soon adopted a style of dress that gave them a lanky, boyish silhouette. The flapper’s skirt was short and streamline, which gave women an excuse to part with layers of undergarments. To ensure every curve disappeared, women would bind their chests, harkening back to the days of corsets and demonstrating the extreme and unhealthy lengths to which women will go to achieve the ideal body image thrust upon them. It is pausing to reflect on the practice and to think that women had to literally repress their femininity in order to be accepted. Though for women of the 1920s, a few suppressing undergarments were most likely a small price to pay in exchange for the power these women could dangle over men’s heads. Unfortunately for them, their short time in the limelight would quickly wear out.

How Women's Fashion Changed With the Depression

The crash of 1929 brought everyone’s highballing life to a skidding halt. The flappers had hopefully enjoyed their youthful gaiety while it lasted, for now it was time to grow up. Since the 1930s brought about a notion that thinness indicated extreme poverty, straight boyish silhouettes were retired seemingly overnight in favor of much more natural forms. Waistlines and prominent bosoms returned due in part to the ideal body type set in place by silver-screen starlet Mae West, most likely to the delight of many. Skirts got progressively longer, though backs were left bare for evening affairs. The ideal woman was to be simultaneously curvaceous and slender and in an effort to emulate such a realistic and achievable ideal, women’s clothing was expected to be streamline and form fitting without a single thread out of place. Despite a return to a plumper figure as an ideal sign of prosperity, high fashion took a back seat to the desperate economic crisis. While displaying fine clothes was surely a goal for many to flaunt their wealth and attempt to relive the good old days of decades prior, to fuss over one’s wardrobe simply was not practical for most American women, a sentiment that would bleed into the next decade.

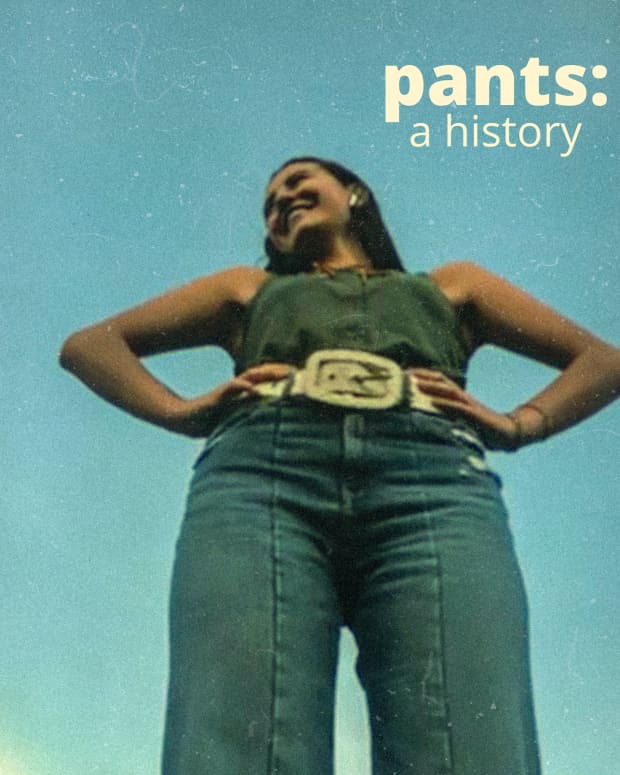

The 1940s were a time defined by war, where men left home and women were required to take over their duties whether they wanted to or not. The war affected everything, including fashion since the need to ration goods and materials impeded on the ability to create specific or unique styles. In an effort to conserve fabric, clothes were simplified in every way possible: fewer pockets and buttons made it onto garments, ruffles or any ornamentation were abandoned, and sleeves and hemlines grew shorter. Many women turned to Mexico to buy dresses since they were cheaper, which inspired designers to incorporate colorful patterns into their clothes. Rationing also inspired many to make their own clothing, harkening back to a simpler time when clothing only served as necessity rather than a luxury. Women got creative, too, as the shortage of wool led them to repurpose men’s suits into women’s attire. The refashioned suits still possessed a masculine silhouette, giving them a boxy appearance with wide shoulders and skirts that did away with the narrow waists of yesteryear. Women began wearing pants as well since they offered even greater functionality and mobility than their skirts could offer. Pants especially rose in popularity since working in factories around heavy machinery while wearing a skirt simply was not practical. Their fashion needed to adapt to their new lifestyle, which meant it was time to bid those dresses goodbye and say hello to a nice pair of functional slacks.

Dior's "New Look" in 1947

Feminine clothes did not completely disappear during wartime for those who could afford to enjoy evenings out, however. Long dresses still ruled the night and were often adorned with sequins to add some sparkle. Homemade clothing may have paved the way to a style that was quintessentially American, but France was ready to return to its traditional pedestal when they finally recovered from the war, at which point Christian Dior introduced a style dubbed “the New Look” in 1947, which was characterized by accentuated waists, billowing skirts and an ultra-feminine silhouette. The need for excess petticoats to pull off the full skirts of Dior’s New Look suggests the style was anything but new, but its clear throwback toward femininity stands as a direct reaction and retaliation to the functionality of wartime fashion. Rosie the Riveter, although born out of necessity rather than empowerment, was a direct threat to men and their place in society. She was traditionally masculine in her style and in her attitude, which meant she had to go.

Photograph of 'New Look' suit designed by Christian Dior. Photographed by John French. London, England. 1947.

V&A John French Archive

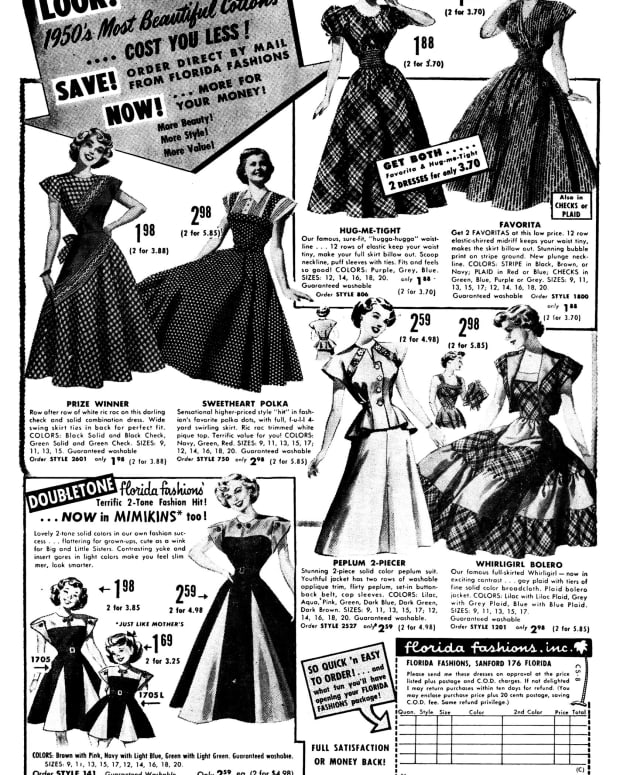

Women's Fashion in the 1950s: Happy Housewives

By the end of the war, family life had never looked more appealing. Society suddenly found itself returning to a patriarchal sense of the home where Rosie the Riveter could not have been more out of place. Now that men were returning from war, there was no reason for women to continue participating in the work force, though that did not stop some women from working regardless of what men had to say about it. To combat the fear that women would steal jobs away from men, propaganda began to be released detailing the wonderful, romantic ideal of a life at home. Many women took the bait, thus returning to their traditional roles and much more traditional fashion. The 1950s carried on the same trends as decades prior with a growing popularity in mass-produced items that made life easier, especially for women’s domestic work.

In 1956, a new style known as the shift dress made its way into many American homes. Initially mocked and dubbed the “sack dress” for its shapeless design, women nonetheless bought the style in droves, apparently attracted to its lack of a defined waistline. The mockery directed toward the dress is a poignant example of when the ideal image does not match the real image of the modern American woman. It stands as a clear example of society’s expectations over women of the time: that they ought to extenuate their femininity through form-fitting clothes.

The dress’s popularity among women could be interpreted as a sign of changing attitudes and a desire for anything but a constricting waistline, but the shift dress was, apparently, only reserved for housewives who thought it easier to go about their daily routine. Career women, on the other hand, preferred to cater to society’s expectations of the ultra-feminine woman by sporting tailored suits over silk blouses – a refined silhouette that was often pulled together with gloves, a hat, and an essential pair of heels. Women continued to burden themselves with girdles, corsets, stockings, slips, and the occasional petticoat. Fashion of the fifties, for the most part, was conservative and constricting – possibly the most constricting it had been since the Victorian era. The shift dress undoubtedly came as a welcome blessing to some, but its presence was certainly an exception to the rule.

Youthful fashion for girls stayed very much in stride with their mothers with flowing skirts, tiny waists and an altogether preppy air. Some edgier styles managed to sneak through the woodwork and challenge fashion norms such as the greaser look or the controversial short-shorts of the late 1950s. In an era where conservatism ruled, it is no small wonder that short shorts were deemed immodest and resulted in revised dress codes across the nation. One could take a step back and chuckle at the authorities of yesteryear while thinking ‘how foolish,’ but the controversy surrounding the style is better suited as a hint of a re-emerging fear of female sexuality, offering up a bizarre duality between femininity and sensuality: that women must be sexually attractive but not sexual.

How Women's Fashion Changed in the 60s

There was something in the air during the 1960s: a flavor of discontent with the way society was treating its citizens that would spill into the next decade. The women’s liberation movement was crawling forward as women began to gain rights legally, culturally, and socially. Feminist Betty Friedan planted a seed for ideological change with her book The Feminine Mystique that inspired many women, especially those who were young and unmarried, to take charge of their own bodies. Sex was once again in style so, naturally, American fashion would slowly begin to reflect that.

Jacqueline Kennedy stood out as the most public supporter of traditional French haute couture, but her imitators were mostly found among the wealthy. The majority of Americans instead embraced a fashion that was minimalist and primitive. A woman of the 1960s would typically wear long, floor length skirts or dresses during the day and mini-skirts when taking on the town at night, which presents and interesting swap from traditionally long and more provocative evening dresses and shorter daytime wear. The switch makes perfect sense considering youth of the decade wanted nothing more than to separate themselves from the older generation in every way possible. The mini-skirt provided an especially strange dichotomy that both objectified and empowered women. The skirt’s scandalous length that had remained unseen until now gave men an opportunity to ogle at gratuitous amounts of bare legs while simultaneously providing power to the women wearing them. The mini-skirt was undoubtedly a sexually charged garment, but in its sexual appeal, it became a source of power for women as well as a sign that modesty was for the old folks.

Fashion During the Age of Aquarius

The growing dissent toward the Vietnam War added more fuel to the anti-Establishment fire, leading to a vehement disregard of societal values and morals that would give rise to hippie-fashion. Instead of conforming to traditional dress norms, hippies often appropriated symbols from cultures outside of their own to inspire their style, giving fashion a deeper meaning as a political statement rather than a simple popular fad. Mainstream fashion continued the trends set by the mini-skirt to bear as much of the body as possible with sleeveless, nearly transparent dresses and hot pants, though the most unique feature of fashion early in the decade was the lack of common conformity. Some women wore long flowing dresses and sandals while others rocked micro-minis and knee-high boots. Some people turned to more conservative, put-together pieces while others continued to strut around in sloppy hippie fashions, resulting in a massive sense of individualism that would begin to ebb as the decade came to a close. By 1977, women were turning to oversized and free-flowing garments that suggested the country desired a return toward conservatism.

Fashion Trends of the 1980s: Be a Man

The shift toward conservative ideals in the 1980s served as a direct reaction to the radical civil rights movements that rocked America. The Supreme Court whittled down previous victories such as Roe v. Wade and affirmative action to the point where the courts seemed to suggest that discrimination was no longer an issue. Conservatism ruled and if women wanted to be taken seriously in the workforce, they needed to adopt a more masculine style. Most people alive to this day still remember or at least have heard stories about shoulder pads no matter how much they want to forget. The interesting, and partially demoralizing, aspect of the trend known as “power dressing”, though, is the fact that doing so was meant to emulate men’s broad shoulders, suggesting one must emulate a man in order to be successful. Power dressing, then, stands as a mockery toward any progress women had made.

The Evolution of Women's Fashion in the 1990s: Into the Future

Androgynous fashion would continue into the 1990s, but a unique feature of styles at end of the century was a seemingly direct parallel of the previous century’s end. Where women of the 1900s strolled about in flowing skirts that grazed the floor, women at the end of the twentieth century and beyond bared every inch of skin they could without violating public indecency laws. Such trends continued into the twenty-first century in varying degrees, some mild and some more extreme than the rest. Two trends worth noting in this most recent era are the trend of transparency in several different garments – most notably blouses and skirts – and the large presence of studs decorating everything from shoes to headbands to jean shorts. Artist Danielle Licea noted that studs are the closest thing women will get to possessing armor to protect themselves in a world so plagued with violence. On the other hand, transparent clothing that displays colorful bandeaus or simply a woman’s bra under the garment can either be interpreted as objectifying women, or it could be seen as embracing women’s sexuality and a move toward a healthier stance toward body positivity. Though it is fascinating to watch how fashion reacts to the social climate surrounding it, it is perhaps far too early to pass judgment on the greater influence fashion while said fashions are still alive and strong.

Perhaps it is time to return to and question that old adage once more: clothes make the man, they say. While it is true that men’s fashion held a level of importance amongst American society, its significance pales in comparison to that of women’s fashion, which altered so radically and much more frequently than men’s clothing. Women’s fashion has constantly fluctuated between practicality and vanity. It has taken on many forms, many meanings and has been received with mixed feelings by their contemporaries. It has been used as a tool to conform to the societal mold as much as it has been used to challenge and break it, resulting in a colorful history that is still and will continue to change as long as fashion remains a fundamental extension of one’s identity.

Referenced Works

- Banner, Lois W. Women in Modern America: A Brief History. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1995.

- Blanke, David. American Popular Culture Through History: The 1910s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Fukai, Akiko. Fashion : a history from the 18th to the 20th century : the collection of the Kyoto Costume Institute . Los Angeles: Taschen, 2006.

- Kunzle, David. Fashion and Fetishism: a social history of the corset, tight-lacing, and other forms of body-sculpture in the West. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Littlefield, 1982.

- Marty, Myron A. Daily Life in the United States, 1960-1990: Decades of Discord. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997.

- Sickels, Robert. American Popular Culture Through History: The 1940s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

- Wilcox, R. Turner. Five Centuries of American Costume. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1963.

- Young, William H. American Popular Culture Through History: The 1950s. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Comments

yug7hygyuyu on February 10, 2020:

cool

Bidoludünya on October 30, 2014:

Wonderful

Bidoludünya

http://www.xn--bidoludnya-geb.com/

Bridget (author) from California on October 22, 2014:

Wow thank you everyone for such positive comments! I'm so glad you all like the hub!

Pinky de Garcia on October 22, 2014:

This article is better than a music flashback. While reading your hub, I feel like living in the past.It's good to know the fashion of my great grandma.Thumbs up!

Bridget (author) from California on October 20, 2014:

Thank you! It amazes me too, that there is so much unique content and creative minds here. I'm glad you enjoyed my piece!

MarieLB from YAMBA NSW on October 20, 2014:

Hi #Birdie Ryan, what a refreshingly different topic. It never ceases to amaze me [I have not been here long either] what a variety of people and of topics there is on this site. As time goes on I am realising what a massive task Admin must have to keep us in line.. ..ha!Ha!!

Back to your article, you have given me such an insight into your world. Beautifully done. Will look forward to more from you.

Besarien from South Florida on October 19, 2014:

I love fashion and especially the history of fashion. I hope you keep adding to this hub!